Artist INSA Takes Us from Grafiti to GIF-iti, NFTs to Large-Scale Works Photographed by Satelite

Photography by DAN WILTON

I meet artist INSA at a pub in Knightsbridge, London on a Friday afternoon. It’s one of those historic spots decorated with wood paneling and stained glass windows. He is seated at the bar getting a round in, with fresh paint still on his hands from his latest project around the corner. We exchange a hug and a mutual complaint of exhaustion, “let’s give it an hour, see how we go.” Within 10 minutes, the art world is being put to rights and it keeps us sitting there for the next four hours.

I meet artist INSA at a pub in Knightsbridge, London on a Friday afternoon. It’s one of those historic spots decorated with wood paneling and stained glass windows. He is seated at the bar getting a round in, with fresh paint still on his hands from his latest project around the corner. We exchange a hug and a mutual complaint of exhaustion, “let’s give it an hour, see how we go.” Within 10 minutes, the art world is being put to rights and it keeps us sitting there for the next four hours.

What started as a feature on the pioneering strides of INSA into the metaverse, ended with a much deeper, human conversation on desire and mortality. He talks about his avid respect for authenticity and uncomfortable relationship with commodity culture; his great love of process and absurdity without limits. Delicately balancing the fuck-you-attitude of DIY culture and perceptions of the “sellout” artist, he allows an unprecedented peek beyond the self-termed “shellfish cunt” and the obnoxious tracksuit-wearing airline passenger he perceives himself being sometimes.

Over the last two decades, INSA has moved through graffiti culture, street and contemporary art to become one of the most progressive artists in the scene exploring art as commodity, through digital and public space. The INSA world is a place of extreme contradiction and indulgence. Flying first-class, he collaborates with a global network of brands, while also designing Lycra catsuits and slingshot bikinis. And he eats shellfish at every opportunity.

Born in Leeds, he began painting at age 11 with two goals: get to London to paint graffiti and never get a job. He fulfilled the former in the late 90s, when he credits legends such as Astek for supporting his introduction to the scene. He recalls the pure joy of raw and authentic artistry with the writers of that time, “to be in graffiti you had to work hard to earn respect. It was a love/hate relationship but there are parts I owe my life to. For outsiders, graffiti gave us a vehicle to communicate and connect with people in a way we never had before.” Painting on the streets at night, he studied at Goldsmiths’ College during the day studying conceptual design. An oxymoron he believed to be complete garbage at the time but ironically has now come to define his creative practice. “Design is always functional. I work to overthink it and then strip it of purpose.”

Over the years, he developed notable stylistic contributions to walls across the world. From intricate 3D letter writing, to his Graffiti Fetish icons to the industrious process of painting and repainting images to produce gifs. Waves of disillusionment drove him towards new perspectives and aesthetic revolts that would reoccur throughout his long and unpredictable career. “I had been painting graffiti for a long time. I had gone to prison for writing letters and there was a lot of violence with a particular negativity towards anyone doing anything different. My girlfriend was pregnant at the time and I’d just had enough. Stylistically, I had hit a ceiling and the imitation of what I was doing was feeling more present.”

He wasn’t the only one. He recalls the zeitgeist sweeping Europe of artists (particularly from Barcelona) transitioning from letters towards logos and icons. Artists were moving away from the scene and more towards the artistry. “What is the least graffiti thing I can do?” This is how he moved from painting letters to pink high heels.

Referring to his now legendary work Heels(Pink), “…people liked the shoes. For the first few years, they assumed I was a girl and I really liked that.” Under the gender-fluid alias of INSA, he’s escaped categorization both as a man and an artist, reveling in the confusion it brings to the audience and his peers. The Heels work was a renewed vehicle of rebellion. Through it, he explored power, lust and objectification to push limits of his own understanding using fetish, both in process and in practice. “I wanted these icons…my ‘signatures’ to be everywhere, remnants perhaps from my graffiti mentality.”

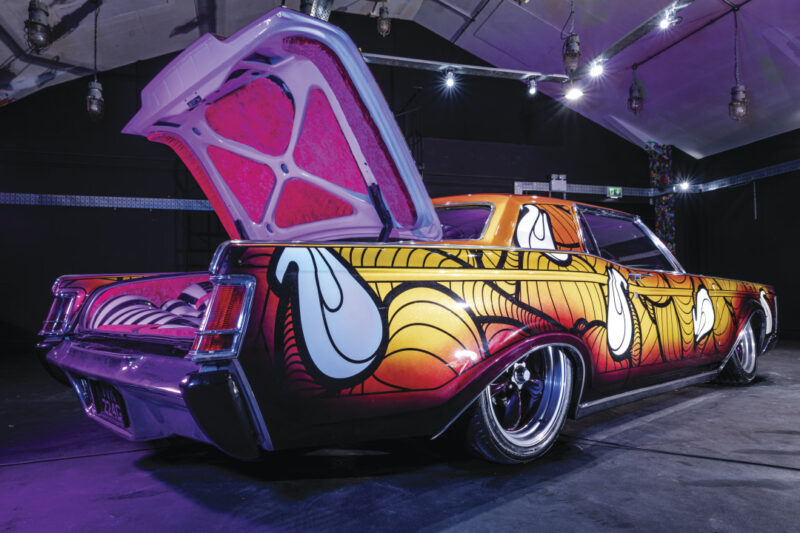

Visual inspiration for these icons came from early 90s hip-hop videos, with iconic sirens like Ice T’s wife, Darlene. In 1988, Darlene had been featured on the Ice T’s POWER album cover dressed in a slingshot bikini and wielding a gun. He recalls the raw and aggressive nature of the portrait as a young man; the male gaze, feminist response, a wife and a woman. She was the definition of control and provocation. This energy was later considered through an absurd prism of objects. Sneakers, bikes and cars; contemporary vehicles of power and status whether someone occupied them or not. The heel became a concept considering dominance of space and the self. That work kicked opened doors in his early artistic career. Exhibition invitations followed, sales and new audiences beyond walls came soon after. His ideas began to expand. “If I can do a heel, can I make a shoe? Can I start a high heel company? How far into absurdity could this go?”

The 3D graffiti was intricate and technical, but the heels; they were the antidote.” Before long, another wave would crash, bringing with it a new direction. “How useful was I being critiquing objectification by contributing more sexy imagery? Maybe not very.” This next moment of transition collided with a crushing revelation in his family life.

INSA had turned down project proposals for years to live that broke, romantic artist life often conflated with “integrity.” This changed in 2012 when his second child was born with multiple disabilities. The impact on his life and his family was profound. Unable to change the reality of his son’s condition, he did activate the power he had over their financial situation. He started saying “yes” to larger proposals. And the more he did that, the more interest there was in collaborating at scale. A contradictory path emerged. “How can I get paid?”—collaborations with the world’s biggest brands, commissions and merchandise–and “how do I make things that cannot be bought?” His answer was GIF-iti.

GIF-iti is a method of painting and repainting the same image with incremental changes, documenting the process and then lining up the stills to reveal an animated gif. While destroying the original work of the public space, his analog process lives on in the digital world. Coinciding with the onset of social media, the introduction of the platform had a significant impact on catalyzing his reach.

“Painting was easy, even when it was hard.” He reflects on the privilege of physical difficulty versus the enormity of his son’s experience. Painting became a literal manifestation of this respect, if he was painting…it had to be important. This sentiment caused an unparalleled level-up for both the scene and his practice. People often take a step back when faced with immense pressure. INSA zoomed out so far, he ended up needing to rent a satellite. For one client collaboration, he painted four giant murals equaling 154,774 square feet of real estate in Rio de Janeiro over a four-day period. Each work was then photographed via satellite and merged into a one-second gif that broke some sort of record in 2015 for the “largest animated painting ever created.”

Evolving technologies have always been close to his practice. He speaks passionately of the freedom of web 1.0 technology and the purity of access to raw information. Then, the capitalist corruption with web 2.0, with its shift to internet marketplace and now of web3 as a ray of hope. Evolving AR, VR and NFTs have returned “play” to the digital space.

Heels were fun, GIF-iti was hard but a joy. I always found money uncomfortable but painting and destroying my works in public space for the gifs meant it couldn’t be commodified. There was a freedom. They were for everyone to enjoy. NFTs are the Wild West and they really fucked with my ideology, it took me a minute to understand my response, so I waited…I want to play a longer game.

This year’s UBS Global Art Market Report includes NFTs as a significant area of study via the decentralized web’s blockchain. While acknowledging rife speculation, they report sales growing from $4.6 million in 2019 to a staggering $11.1 billion in 2021. INSA expresses his distaste for this global cash grab disguised as an emerging digital portfolio. “It wasn’t about the art, it was about the money. There are parallels here with street art and graffiti, the Banksy-effect and money subsequently destroying the subculture. NFTs fall victim to that same hyper acceleration.”

Whether in digital or physical space, INSA works to innovate at all costs. For NFTs, his approach to GIF-iti gave him an edge, a way to exist in both realms. His first NFT contribution was the INSALAND Members Jacket which—if purchased as a digital asset—granted an opportunity to be one of 10 randomly-selected owners of the tangible version of the jacket. To date, he has completed a handful of NFT drops and is keen to expand the effort with a series of artist collaborations for unique one-offs.

INSA is an agile creative innovating on the outskirts of possibility. His unquestionable technical ability, groundbreaking projects and online development secure his position in a space which, true to form, defies categorization. Public art has shifted as society continues to redefine both terms. We have images ascending their physical lives on walls to achieve an ethereal immortality in the clouds.

It seems over the next 10 years, the disparity between the avatar and the creator will continue to grow. INSA can take up full time residency within a cloud, as he challenges the expanding metaverse with memories of Darlene at the same time his earthly counterpart is with family by the sea, munching on shellfish in a tracksuit.

@insa_gram