Hailing from Dublin, the Indie Rockers of Fontaines D.C. Stay True to Their Roots During Rapid Growth

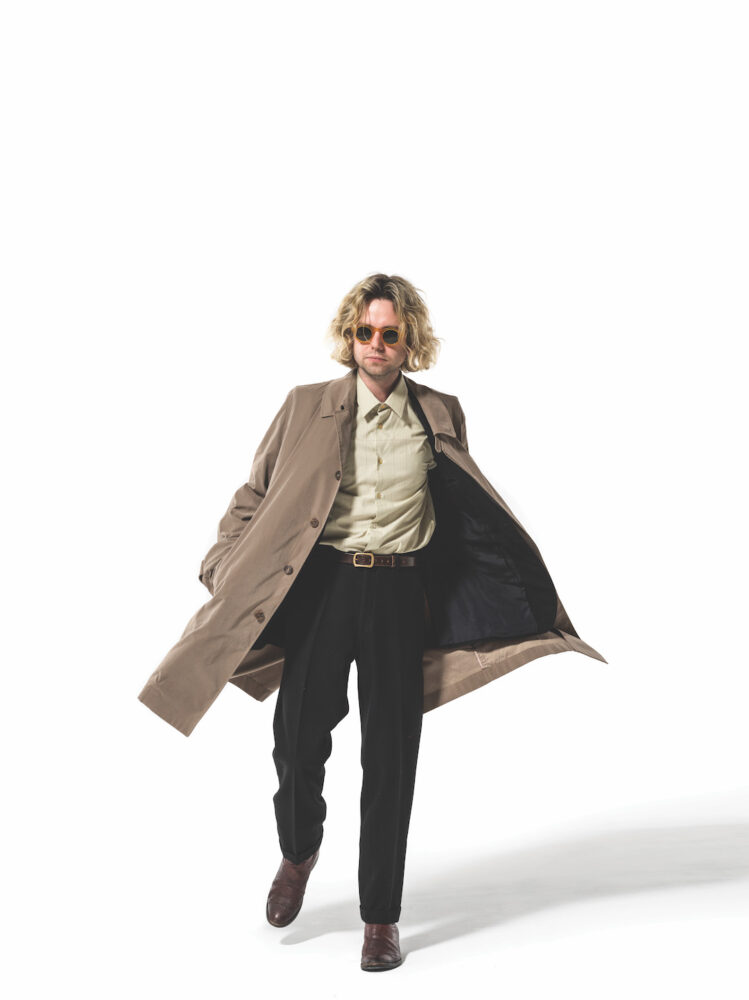

WORDS by PATRICK CLARKE

PHOTOGRAPHY by PEROU

STYLING by DAVID NOLAN

Last August, high up in the Brecon Beacons mountain range in Wales, Fontaines D.C. were approaching a major peak. The band had been booked to play the biggest show of their career as headliners of the prestigious Green Man Festival. A crowd of 60,000 people. Due to close the event’s final eve- ning, the group had spent the preceding two days soaking up the atmosphere, wandering around the crowd, chatting with the occasional fan who recognized them and watching other bands on the bill. “I didn’t even think about the show until Sunday,” says guitarist Conor Curley. “My main worry was whether I could enjoy festivals any more as a punter, but it was such a good crowd.” The atmosphere was buzzing with the spirit of a nation only recently (albeit temporarily) freed from the majority of pandemic restrictions; throughout the summer there had been major doubt as to whether or not it could take place at all.

The band was still apprehensive. Green Man would be the biggest show of their career by a considerable margin. “I am a person who lets the size of a ceremony affect me before we go on stage,” says straight-talking front-

man Grian Chatten. He recalls their show at London’s Brixton Academy in early 2020. An iconic venue certainly but a relatively smaller capacity of five thousand people. “I was nervous then. I was concerned that as a performer I wouldn’t be able to fill up a space like that,” he admits. Even when the band had just started gigging outside of their native Dublin, performing to pub crowds barely breaking double figures, Grian had suffered stage fright. “When we did our first London show, in front of about fifteen people, I got so nervous beforehand that I didn’t eat all day and drank so many cans I almost fell off stage and completely ruined the gig.”

Fontaines D.C.’s performance in Wales did not just deliver. It felt genuinely epochal. Grian was a charismatic and commanding presence and the rest of the band were ferocious. There was no need for Grian to rely on the tropes of any arena-sized indie rock predecessors. Instead he exuded nothing but sheer comfort. “In truth I just got lost in it, taken away,” he says. Afterwards, the band shot back to their trailer, blasted OutKast from the speakers and jumped up and down in celebration like overexcited kids. “No one was pretending it wasn’t a big deal,” Grian says.

“I feel like we proved something to ourselves that night,” says Conor. “I had always figured we were a 100 to 200 capacity band that had been blagging it up this whole time and that one day we were going to get found out. But after that show, I bought into the idea of our songs being able to fill a bigger space.” In the months that followed the group embarked on their biggest headline tour thus far, including a London show at the enormous and iconic Alexandra Palace Theatre. “It makes a potential future of being a band that play to crowds like that seem a lot less uninteresting,” Grian observes. Until then, he’d attached the band to a certain “ethos,” he says. “We wanted it to stay to a size where you can see the whites of people’s eyes in the crowd. My main concern was that I wouldn’t be able to, personally, as a performer, be able to fill up spaces like that without compromising what I’ve built upon.”

It’s worth remembering that it was only five years ago that the band were playing that messy London pub show to barely a dozen people. “When you first play to an audience that’s much bigger than what you’re used to, it’s kind of like being the host at a party where you bring a load of different groups of mates together and you’re concerned about them all getting along,” Grian continues. “Are the people at the back having a good time? I’ve felt myself tempted to take the mic pole out of the stand and do a Freddie Mercury, but to me that would be pan- dering. It would be at the expense of my own performative integrity. I just had to learn to be present and alive.”

Identity has been on the band’s minds since the release of their last album, 2020’s A Hero’s Death. In the time since, all five of the band permanently settled in London. Grian to move in with his English fiancé. It’s a relocation that made them more conscious of their Irish roots, especially when the city started opening up between Britain’s three national lockdowns. In the past, stereotypes about the Irish being lyrical or storytellers would often come up in the press. Especially in the media context of an exciting-young-Dublin-indie-band scene surrounding them in the late 2010s. When they moved to London though, they were exposed to far uglier prejudices. Those of the Irish as drunks, thugs or criminals. Grian was taken aback by just how much “covert hostility” they faced, “especially after a certain time in bars.” It was the kind of prejudice they had naively considered a thing of Britain’s past, more synonymous with The Troubles conflict or with the waves of immigration in the first half of the last century. “We weren’t prepared. We weren’t told that it was still a thing.”

Only recently, he continues, “Tom [Coll, drummer] told me he was in a cubicle in a pub toilet. Two fellas came in and he heard them say: ‘There’s a lot of fuckin Irish out there today. You’d better check if there’s any bombs first,’ and they were laughing to each other.” Their experience includes endless jokes about the IRA and terrorism, as well as the potato fam- ine or the Irish’s supposed tendency for violence. There were micro-aggressions, like demands from complete strangers to either lessen their accent to be more easily understood, or to ham it up in order to parrot phrases as if they were some kind of performing leprechaun troupe.

“When you move to any city, there’s always a desire to be let in by the place,” says Conor. “In London there was an indifference that made us realize that maybe this isn’t a place where we want to be fully let in.” Instead, the band’s pride in their roots only intensified. “My reaction was to covet that identity that’s being rid and to feel closer to it,” Grian continues. “There are times where I’d get off on being in a group of Irish mates, knowing that there are these prejudices being thrown at us but that we’re a tight unit in spite of that. There’s a bit of an edge to going out in London when you’re a group of Irish people. You still get called ‘fucking Paddys’ but there’s some- thing exciting about that because you feel like you’re on the edge of changing someone’s perception of your culture.” On the flipside though, was homesickness. There were nights falling asleep that images of random Dublin streets, locations “I’d never even thought twice about before,” that popped into Grian’s head and kept him awake for hours.

There was guilt too. About leaving behind a motherland in turmoil. From afar, they watched Ireland get hit hard by the pandemic. The nation’s already weakened health infrastructure–there are still only 300 intensive care beds in the entire country–buckling under the pressure. “The way the government is handling stuff over there is nothing short of an outrage,” says Conor. Living in London, Grian says, “I had the privilege of not having to think about all that shite but I think I’m done with that now. It’s not fair for me to not have to think about them but still sing about a country I supposedly love.”

Fontaines D.C. have always been influenced by Ireland. The initials at the end of the ” band’s name–added in their early years to avoid conflict with LA band, The Fontaines–stand for Dublin City. Their debut album Dogrel, released in 2019, was teeming with vividly painted characters from the Irish capital: a chain-smoking republican cab driver or a woman with “a heart like a James Joyce novel” on breakout single “Boys in the Better Land”, for example. It opens with territorial swagger: Dublin in the rain is mine/A pregnant city with a Catholic mind and ends with a winsomely scruffy ballad called “Dublin City Sky”. As they began to work on their third album, the intense mix of pride, guilt and guardedness that came with their upheaval to London, meant that their heritage started to influence them with a newfound depth.

The change was subconscious at first. At one point, Grian started writing a straight-up love song, “I wanted to call it “I Love You”, I thought it would be an exciting challenge to write a song on such a clichéd and well-worn title and sentiment and to try and make it interesting. Lo and behold, it turned out to be about Ireland.” Another song, “Roman Holiday”, began as a song about Grian’s English girlfriend, but ended up loaded with subtext relating to their respective nationalities. Irish listeners will enjoy meanings of lines like “I will dart into town” – a subtle reference to Dublin’s dilapidated train service known as The Dart. Or recognize the significance of the lyrics like, Our day will come (Tiocfaidh ár lá), a slogan used by high-profile members of the IRA during The Troubles.

These tracks feature on the album Skinty Fia, an anglicized version of an Irish expression that drummer Tom’s great aunt was fond of using. She was a Gaeltacht, one of a rapidly dying breed of people who primarily speak the critically endangered Irish language. Loosely translated as, the damnation of the deer, it’s roughly analogous to the well-uttered English phrase, for fuck’s sake. For Grian, it’s also a symbol for what the album’s about. “The aggregation or reincorporation of Irish culture…it’s about its mutation and how it exists in another realm. Like how in Boston in America they dye the rivers green [on St. Patrick’s Day] and all that mad shit. That’s a good example of skinty fia.” The album opens with the track, “In ár gcroíthe go deo”, (in our hearts forever), the title repeated in a choral chant in the background through the entire song.

“In ár gcroíthe go deo” is also indication that the album is some step forward instrumentally too; a pounding industrial beat fizzing its way in under the elegiac choral refrain at the song’s halfway point. Electronics return even more prominently on the title track, which borders on a 90s drum and bass beat, while the yearning “The Couple Across The Way” is

at another extreme entirely. A swooning ballad consisting of simply two chords Grian figured out on a second hand accordion he was gifted for Christmas. Their second record A Hero’s Death was a dramatic shift in itself when it arrived barely a year after their debut–a gap that would’ve been shorter had their contract not prevented them releasing albums less than 365 days apart–stretching the scrappy indie-rock of their debut into sprawling and droning post- punk, but Skinty Fia explores beyond guitar music entirely. “To me it’s just more exciting,” says Conor. “Before, maybe we were just trying to use influences that were in our realm.”

It’s barely five years since the band formed and they’ve released three different full-length albums in four years and might soon be onto their next Conor explains. “Me and Tom were working on something in the rehearsal room the other day. I was just testing out an amp and playing some chords and straight after that I thought, ‘we should write another album.’ That gut feeling is quite addictive.” Their pace, Grian says, is driven “by nothing more than curiosity, really. I think musically, we get bored of things quite quickly.”

The band’s debut album was a huge hit, breaching the Irish Top 5 and the British Top 10, critically adored yet they felt no pressure following it up. “I think one thing that we’re particularly good at as a group is shutting out voices, shutting out critique generally, good or bad. That frees us up creatively to push the boat out.”

Talk turns to “Boys in the Better Land”, Dogrel’s lead single and something of a signature tune. When they played it at Green Man, the atmosphere spilled over into outright mania. “Because it’s our biggest tune,” says Grian. “Anything that we write similar to that, by default, is boring. That’s the zero on the pH scale, and we’re trying to pull that left and right, trying to stretch it.”

Nevertheless, three albums in and now established as bona fide festival headliners, the band have taken the odd moment to look back at what is now a considerable discography. Different they may be but their three records also carry an identity unique to Fontaines D.C. And influence they credit to acclaimed producer Dan Carey, who worked on their first two albums in his home studio in South London, and their third in rural Oxfordshire. “He’s never stayed the same,” says Conor. “That’s something we took from him, the art of change, how if you change your aim a little to the left you’re going to go somewhere different.”

Beyond that though, there’s an essence to all of their music that has remained the same regardless of the speed and scale of their transformations. “Spiritually all our albums are connected because, though I could be completely delusional, I think we have a lot of character in them all,” notes Grian. “I see that song ‘The Couple Across The Way’ as having the same kind of spirit as ‘Dublin City Sky’ or ‘Boys in the Better Land’. It’s what you get when you simmer those tunes down to their most reduced state.” And ultimately, that essence cannot be separated from the band’s native land.

@fontainesband