Interpol on Developing and Touring Their Lastest Album, ‘The Other Side Of Make-Believe”

Words by Rhian Daly

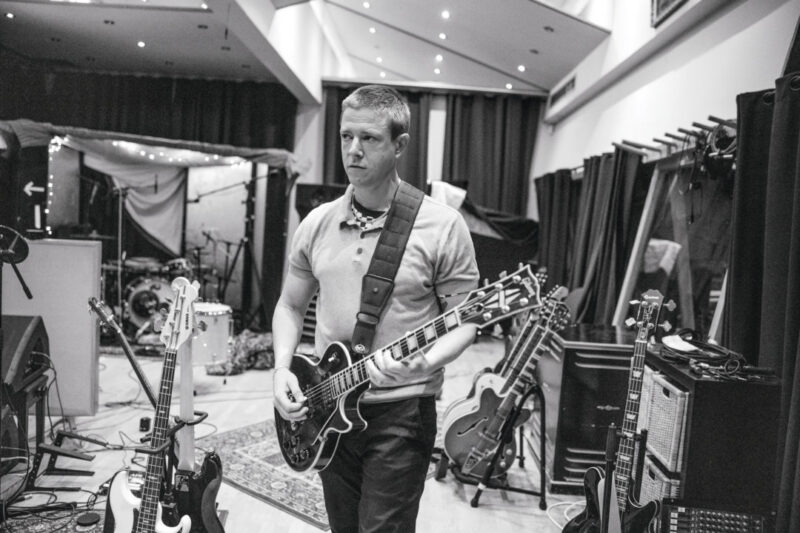

Photography by Atiba Jefferson

When Interpol were working on 2018’s Marauder, things got so block-shaking loud, the NYPD booted them out of their rehearsal space. But two years later, as the trio began work on their seventh album in 2020, The Other Side Of Make-Believe, things couldn’t have been more different—or quieter.

Locked down in Spain was guitarist Daniel Kessler, in Scotland, singer Paul Banks and in the US, drummer Sam Fogarino. The band—like everyone else—were forced to remotely get their work done using technology. With “battling the loudest thing in the room”

(aka Fogarino’s drums) no longer necessary, they slipped into more comfortable modes that yielded something not often associated with the typically morose group: positivity.

“I was writing vocals at home in a comfy chair in a bedroom and I think it allowed me to explore a little bit more of a delicate, melodic approach to singing,” Banks recalls, sitting alongside his bandmates on a black leather sofa in a dressing room in Salt Lake City. “That, in turn, opened up different themes emotionally as well [things that were] more intimate, vulnerable and the outcome is an optimistic, uplifting feeling.”

It’s an atmosphere that strikes as soon as you press play on the new record. Opener and first single “Toni” glides along on a light, airy piano melody, Kessler’s sonorous guitar weaving around it: I’d like to see them win/It’s my kind of aspiration like it’s going in the

right direction, Banks declares on its chorus, buoyant and upbeat.

While fans might be caught off guard by the positivity that runs through The Other Side Of Make-Believe, the singer shrugs off the surprise. “A lot of times with me, lyrics feel like they already exist and I just find them through the fog,” he shrugs. “It’s like that’s what the song wants to be and I don’t really evaluate it beyond that.”

After initially sending files back and forth, Interpol finally got back in a room together in early 2021 when they rented out a house in the Catskills of New York. Afterwards, they headed to London to record with acclaimed producers Flood and Alan Moulder (the latter also mixed their fifth album, 2014’s El Pintor). As work continued, a “sense of purpose” began to grow. “It felt almost like we were making our first record,” Kessler recalls, highlighting how “deeply invested” the whole band and their producers were in what they were making. “You can’t take that for granted when you’re on your seventh record. No one was like, this is good enough. It was really exciting that we all still felt that way.”

After initially sending files back and forth, Interpol finally got back in a room together in early 2021 when they rented out a house in the Catskills of New York. Afterwards, they headed to London to record with acclaimed producers Flood and Alan Moulder (the latter also mixed their fifth album, 2014’s El Pintor). As work continued, a “sense of purpose” began to grow. “It felt almost like we were making our first record,” Kessler recalls, highlighting how “deeply invested” the whole band and their producers were in what they were making. “You can’t take that for granted when you’re on your seventh record. No one was like, this is good enough. It was really exciting that we all still felt that way.”

In parts, the record ponders shifting truths in modern society as when Banks sings on the melancholy chime “Fables”: It’s time we made something stable […] All is lost, the time beyond the fables. But overall the frontman stays true to the album’s overriding hopefulness. “I think it’s a super crazy, interesting moment in time,” he says, lining up two options for how he sees us progressing from here. “Either something comes along that’s corrective, where we get back to shared societal concepts of what is what. Or, everything gets super fucked up and then has a phoenix-from-the-ashes recalibration and we’re back on track.”

While we wait to find out exactly how humanity’s future pans out, Interpol are getting back into the regular routine of a modern band. When we speak, they’re 5 dates into a North American tour previewing their new record and they’re feeling enthused about being able to share the fruits of their labor with a live audience again. “Every night I’ve been really, really happy because the reaction at the end of the new songs has been super enthusiastic every time,” Banks smiles. “It’s been a nice kind of trust fall feeling for me with the crowd and feeling like they’re catching us.”

We’re all a bit more, ‘in the moment.’ We make a record, tour, get back to life, then see where we’re at. It’s a good way to go.

As well as strengthening their bond with their audiences, the fresh cuts the band have been airing in their setlists have also given Interpol’s relationship with their older material a refresh. Although all three members say they still love the opportunity to air some of their best-loved songs like “Slow Hands” and “PDA”, at times, it can get “a little burdensome, but when you put them back into a set [with new music], some of the excitement from the newer material bleeds into them,” explains Fogarino. “One hand washes the other and the excitement reinforces material that you’re very familiar with, let’s say.”

The era in which some of those more well-worn songs first found popularity has become a fountain of nostalgia in recent years, first with Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011, journalist Lizzy Goodman’s oral history of the New York indie scene in the 00s and now with “indie sleaze” revival. As a band who were at the heart of that period, all the talk around its resurgence must have caught Interpol’s eye?

“I was aware of an Instagram account that had posted a photo of me that I really like, holding a digital camera in front of my face,” Banks says. “That account was called @indiesleaze but that’s the first and only time I’ve heard the term so it’s news to me there’s an actual moment happening with that.” The band might be oblivious to the scene but that doesn’t mean they’re against it. “Sounds cool, though,” the frontman adds nonchalantly.

Nostalgia isn’t something the trio like to indulge in much but they’re not a band that begrudges people looking back. “There’s always going to be a great sense of curiosity—especially for young music fans—of what came before,” Fogarino reasons. But thanks to how easy it is to access the resources needed to discover the art that defined past decades, the drummer is preparing for the cycles of nostalgia to only “get more intense, I think we should all get used to it, really.”

This summer marks an anniversary for the trio that will likely cause a fresh bout of wistfulness: the 20th anniversary of their seminal debut album Turn on the Bright Lights. While the sticksman says he doesn’t want to get drawn into “nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake,” he shares a moment of pride for the work he and his friends have made together: “Personally speaking, when I pass, knowing that I’ve been on these records with these guys sitting next to me. I’ll be very happy with my contribution and what I leave behind.”

Over the last couple of years, the world’s medical, social and political turmoil has sometimes shaken that conviction, leaving Interpol—like many people—questioning the purpose of their jobs. Fogarino murmurs in agreement, sharing the somber thoughts he had at the height of the pandemic when he felt as though he, as a musician, couldn’t contribute to what was important. “I really felt like ‘my hands are tied, playing a drum pattern…isn’t going to help anything right now.’ It was interesting to admit that where I could jump to wouldn’t do any good. It did seem really bleak.”

While questioning the values of creative work though, they hit upon the power that music can actually possess. “It’s more important than ever to have art. Things like music and comedy give voice to people who want to speak up against what’s fucked up in our societies,” notes Banks.

Now settled in their position as elder statesmen of indie, Interpol don’t feel the need to put any pressure on themselves to be constantly working on something new. They know it’s time to reconvene for their next chapter when they feel a “gravitational pull”, as Fogarino puts it. “We never make plans,” adds Kessler. “We’re all a bit more, ‘in the moment.’ We make a record, tour, get back to life, then see where we’re at. It’s a good way to go.” Reinvigorated and reunited with a brilliant new album ready for release, it’s hard to disagree. Right now, the future of Interpol looks as bright as Banks’ newfound lyrical optimism. @interpol