Get a Glimpse into Church Studios Fabled Recording Space That’s Hosted Florence Welch, Adele and Many More

WORDS by OLIVER KEENS

PHOTOGRAPHY by TOM MEDWELL

You wouldn’t think a music studio in a 170-year-old holy house at the end of a street called Crouch Hill could be one of the most important places in the history of modern British music. But you’d think wrong. Operat- ing for close to 40 years, The Church Studios is a fabled recording space that’s hosted the world’s biggest artists. If you record there, consider yourself the unde- niable cream of the crop.

Furthermore, if you find yourself working with the studio’s current owner Paul Epworth, then consider yourself in hands safer than a midwife’s. Arguably nobody in the last two decades has done more to keep British music punching above its weight than Epworth. In 2004–his breakout year as a producer–he helped catapult Bloc Party, The Futureheads and Maxïmo Park into the spotlight before going on to work with Florence + the Machine, Plan B and Kano before the decade was out. His work on Adele’s 21 changed everything for him. As we talk in Epworth’s grand Studio 1 the morn- ing before a session is due to start, he jokingly refers to his temple of sound as “the house that Adele built.”

The studio is an unassuming fixture in an impossibly genteel and pleasant pocket of North London called Crouch End. Comprising three studios in total, the modern ones feel “like something from 2001: A Space Odyssey as Faris Badwan of The Horrors described. The band is signed to Epworth’s Wolf Tone label and recorded their album V at the studio. Glass Animals, the first British band to top the daily global Spotify streaming charts, recorded their albums How to be a Human Being and Dreamland at The Church. The first ever band signing to Wolf Tone, they were developed within The Church and both albums were executively produced by Epworth.

Other rooms “are almost medieval, although there are more synths than antique weaponry.” While it occupies around half of the building (the other half is still a working church, which doesn’t sonically encroach on the studio except at Easter when they get the crowds in), it’s still an incredibly lowkey presence on a street that boasts three hairdressers and a dog groomer. Yet somehow the list of rabble-rousing icons to use the facilities flies in the face of the calm surroundings: Madonna, Nick Cave, Coldplay, U2, Lana Del Rey, Usher, Kendrick Lamar, Dave, FKA twigs are among the names on a very long list.

Seconds after walking up the stairs and entering Studio 1, I understand what makes it such a prolific destination. Maybe the nearest thing we have to a modern Abbey Road? The almost outlandish vastness of the space is remarkable. Music studios tend to be small, dimly lit and slightly squashed places. The Church is the opposite. The main room is blessed with a biblically high ceiling. “The ten- sion goes right up there” says Epworth, pointing to the heavens. Natural light pours in during the day, which supports the circadian rhythms of those in the hot seat. And if you need to escape for a while, there’s always a spire to climb and a church belfry to hide out in.

There’s also none of the “goldfish bowl” environment that’s common to most recording studios: performers in one room working to nail it as they’re observed, sometimes intimidatingly, by producers on the other side of a thick pane of glass. “Artists are self-conscious enough already” reckons Riley Mac- Intyre, an engineer at the studio. “Everyone works in open plan now,” says Epworth, who has configured the studio’s main room to have no division between performer and producer. “Here, you can stop the music and talk to someone or go over and get involved. It’s the antithesis of most sterile studios.”

The reason for this lack of divide is in large part because of the studio’s behemoth mixing desk: two EMI Neve consoles from the 70s stuck together to create a hybrid monster that cannibalizes two of the five Neves ever made. One of which used to live at Abbey Road and was used by Pink Floyd on Wish You Were Here. Now they’re situated roughly where an altar would be and bring forth what Epworth calls an “openness to the sound” of the many records blessed at The Church Studios. “They’re the best consoles in the world,” shares Epworth. “Whatever you put through–vocals, drums, synthesizer–it just sounds good.”

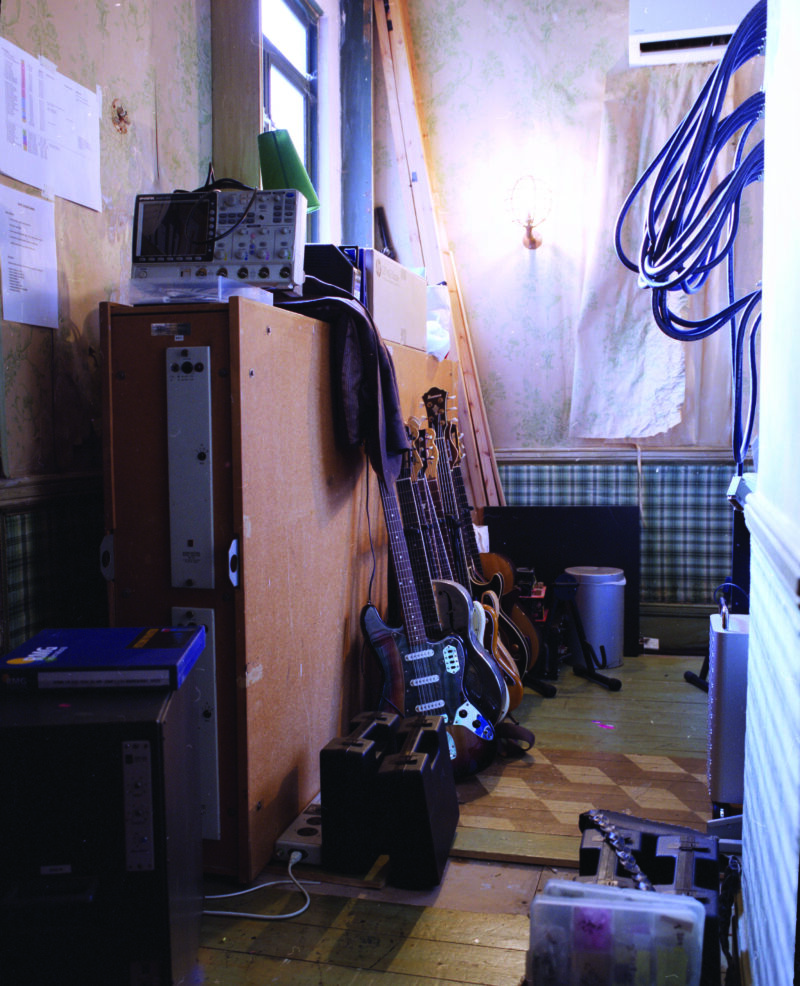

Imagine a cross between a bedroom setup and the loft from the film Big and you have an indication of the studio’s overall vibe. It’s not polished, it’s not posh. It’s just FULL of stuff. Good stuff. The kind of stuff that causes music makers to gasp at first sight. Crates of guitar pedals sit waiting to be plundered. The walls are lined with a frankly absurd amount of synths, all plugged in and ready to go. Next to the drum kit is a vocal booth, about the dimensions of a shower and festooned so casually in loose blankets and rugs that it feels more like a student dorm than potentially one of the most commanding places on earth.

The studio prides itself that artists and bands never need to hire any instruments in from the outside world. When I test this by impulsively asking for a harp, there’s a bit of chin-scratching before an engineer assures me: “yes, I think we do have a harp.” A lot of the gear has been accumulated along the way by Epworth, who it’s fair to say, doesn’t seem to put up much of a fight when offered an expensive synth or two from a network of private dealers. He even recalls one of particular repute from NYC, known only as “the synth pimp” who could magically get a hold of any keyboard day or night. Delivered within about an hour’s notice by a black van.

Because the recording studio houses every conceivable bit of gear, “there are no excuses when you get here,” explains Epworth. “You can’t say: ‘oh I can’t do this or that.’ It forces you to challenge your process instead.” Given that it can be a high-pressure environment, there’s a nourishing side to running a successful studio too. “When people are bearing their souls, it’s all about making it comfortable for them” says MacIntyre. This means keeping cupboards full of nice crockery, being able to turn rooms into nurseries or spaces for a full-time masseuse, having all the right boozes on tap and knowing where to get delivery during late-night sessions. “People like The Church because we let them feel like this space is their own” stresses Studio Manager Alys Gibson. And it’s true: artists are drawn to it.

But probably the most iconic Church tale happened before Epworth’s time when Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart owned the studio. The story goes that he’d given his pal Bob Dylan an open-ended invite to come down anytime. But then in 1985, randomly taking him up on the offer, Dylan ended up at the wrong address. Asking at the door for Dave, he was told “Dave” would be back in 20 minutes, only for a plumber named Dave to arrive home, bemused that his wife was sitting in his living room with folk-rock superstar, Bob Dylan.

Dave Stewart initially started out in the church’s vestry room, in a building then occupied by stop-mo- tion animators making English children’s TV like Captain Pugwash and Trumpton. “I was walking up the street,” Stewart tells us over the phone from an undisclosed island that’s “3 miles by 1/2 a mile wide…and a guy called Bob Bura popped his head out from the animators and gestured to me to come across the streets. I was wary but he just said, ‘are you looking for somewhere?’ Annie (Lennox) and I had been squatting nearby. I don’t know how he knew.”

Once installed in the small ceremonial nook, they set about writing and completing “Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)”. He slowly took over the space from the animators and it became his own personal studio, a place where both records were made and much fun was had. Stewart tells us about recording the strings for “Here Comes the Rain Again” in the corridors and bathroom of The Church. He also recalls having a double bed up on the balcony which he swiftly removed because it felt “too spooky” and instead converting a side room into a little boudoir writing room with a day- bed for artists. There was also the evening Bob Dylan came over (right address this time) after a show with 50 people made up of musicians and poets for a soirée. There’s another evening Stewart gleefully recalls when Daryl Hall, Clem Burke from Blondie and Joni Mitchell all swapped instruments. “We did it for about an hour and a half,” Stewart recalls. “Joni was really excited about play- ing the drums. She said it was the most fun she’d had in a long time. I always thought that The Church had a certain magic to it. I think it’s in such great hands with Paul Epworth. I’ve visited him there quite a few times and I love the way he’s set up his way of recording inside the big room. You get the full feeling of being in the room with the band playing.”

After Stewart’s tenure ended (singer/ songwriter David Gray took over ownership before Epworth’s reign), parts of Radiohead’s OK Computer were mixed there, as was the incredible sonic milestone that is Loveless by My Bloody Valentine. “We’ve still got the speakers Kevin Shields mixed it on here, wait- ing for him to collect” Epworth points out with a hearty chuckle.

Adele won an Oscar with Epworth for the soundtrack hit “Skyfall” and he also co-wrote the 20+MM selling mega hit “Rolling in the Deep”. Incidentally, the guitar they used to write it sits casually in front of the vocal booth, so casually that I was able to give it a little strum. Even her video for 2015 single “When We Were Young” was filmed in Studio 1, perhaps providing the best encapsulation of the spirit of the place. From the relaxed and informal chat between Adele and her band as she’s getting last bits of makeup applied, to the slow, sweeping cameras that capture her live performance, the video shines a light on what makes the room itself such a star. The high ceiling is there, a mesmerizing jumble of wires spooling out of every device is there, the humble Persian rugs on the ground and the two huge wood-en- cased monitor speakers which flank Adele as she sings are definitely there.

It’s all there in an understated scruffy glory: the peak of modern music, at the bottom of a big hill.

@churchstudios