Vikki Tobak’s Latest Work “Ice Cold: A Hip-Hop Jewelry History” Tracks the Evolution of Bling

ALL PHOTOS courtsey ICE COLD: A HIP-HOP JEWELRY HISTORY

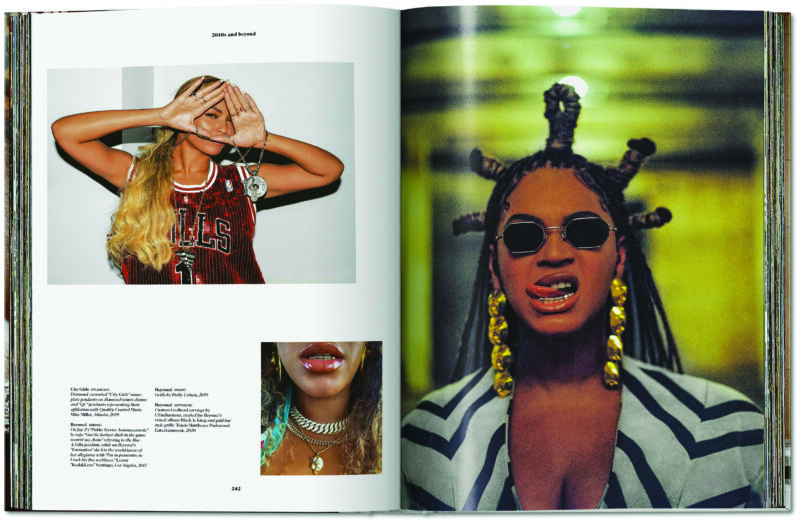

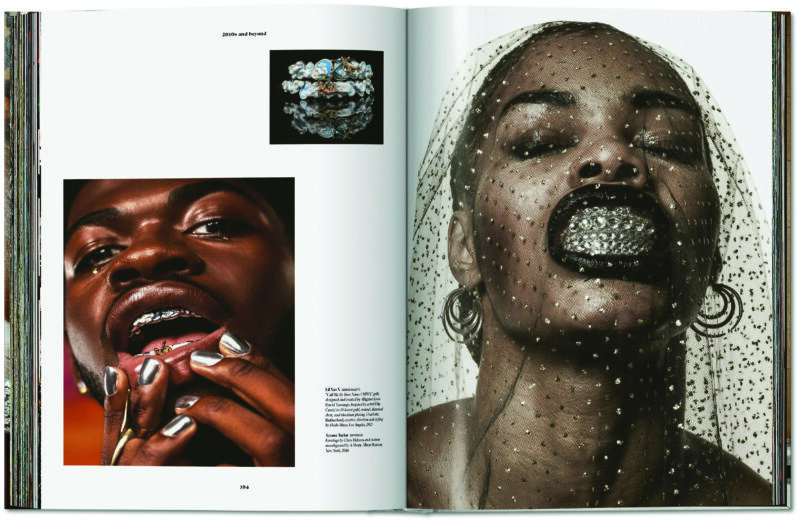

Ice Cold: A Hip-Hop Jewelry History tracks the evolution of bling. Starting with the dookie rope chains and gold Adidas pendants that defined the hip-hop scene of the early 80s to the more contemporary pieces worn by Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion and Tyler, the Creator, Ice Cold details decades of beautiful, outrageous jewelry and those who crafted it.

Written by Vikki Tobak, Ice Cold follows her 2018 volume, Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop, and is the result of two years of research. Featuring essays from the likes of LL Cool J, A$AP Ferg and Slick Rick, its release comes ahead of the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, happening next August.

reaction been?

It’s been incredible. Whenever you put out a book that encompasses this big, cultural, historic thing, you just want to make sure you’ve covered everything. I started with old school hip-hop and talking to people who were actually there, and went right through to the hip-hop of today. Today, hip-hop is not a monolith. Black culture isn’t a monolith. You have so many artists taking on gender themes and rethinking how we present and what we look like. That’s all coming out in the jewelry, from men wearing pearls to chain link styles. All those things challenge the history of jewelry and I knew we had to include that. I think people appreciate having all those things under one roof.

Why do you think jewelry is so important in hip-hop?

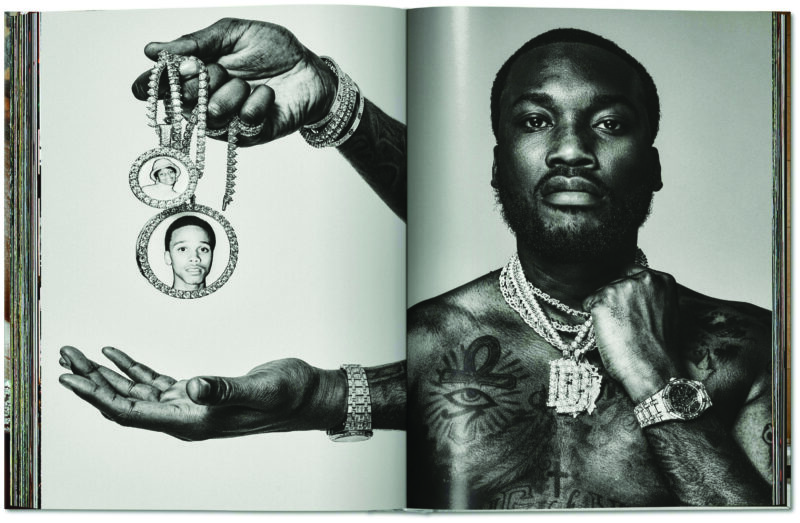

From African kings and the pharaohs to Elizabeth Tailor and Liberace, adornment has always expressed status and wealth. Within the context of race and politics in America, the places and spaces that hip-hop was born out of didn’t have a lot of generational wealth. So hip-hop and Black culture started to use these symbols of conspicuous consumption as a way of saying the American Dream was for them as well. It was about transcending your circumstances. I’m putting it in a very academic way, but we all know that when you come from a place of not having things, when you’re finally able to get those things, it takes on a bigger significance.

Was there any pushback from people?

Here and there. I’d be out in the world talking about it and there’d be a lot of coded language. People being dismissive, saying “why wouldn’t the first thing they buy be a house?” It made me understand that I needed a lot of writing in the book. TASCHEN, who I worked with on Ice Cold, makes such beautiful books and often there’s an introduction, then a bunch of beautiful photography. I was like, “guys, buckle in, because we’re going to have a lot of writing in this book” because it needs that story. That context is really important.

You’ve been around the hip-hop scene since the 90s so you knew what to look for.

Jewelry has always been a part of the fabric of hip-hop. When I was doing Contact High, I was picking apart and analyzing every little detail of each photo, from what the artist was wearing on their feet and their clothes to their hairstyles. I started thinking about how all those little visual signifiers really meant something, but the jewelry was literally the flashiest part.

Adornment and what we wear on our bodies is a story that’s timeless. It’s a very human thing but with hip-hop, you have these other layers of identity status and declaring who you are. Now it has aged. It’s mainstream culture. It’s created millionaires like Jay-Z, Diddy, Beyoncé and Tyler, the Creator. People understand that jewelry is part of this bigger movement of building generational wealth, and having hip-hop and Black culture step into its power.

Did anything surprise you while working on Ice Cold?

Because the book is so celebrity driven, I think a lot of people miss the jeweler side of things. It’s such a hard story to shine a light on because it’s a world we don’t see, but I tried my best to describe the buzz of walking in the diamond district, the craft of actually making the pieces and that whole ecosystem. I also tried to give as much detail about what grade the stones in each piece were, or what the link style was. It’s been great because the jewelers totally embraced this project.

And their stories really surprised me. I knew names like Jacob the Jeweler, Ben Baller and Tito [Caicedo] through lyrics but I didn’t know their stories. I learned that pretty much all the jewelers that service and serviced hip-hop are either immigrants or the children of immigrants. Those two worlds communicate with each other from this place of love but they’re also haggling at the same time. I think they just recognize the hustle in each other.

Do you recognize the hustle?

For sure. My family immigrated from Kazakhstan when I was five. We landed in Detroit, which is very much a working class city but is also full of Black culture and Black music like Motown. That was my entry into Amer

ica, but it was also a very hard city to grow up in. My dream—and I think a lot of other people’s dream back then—was to get out. To transcend our circumstances. The only way to really do that is to hustle your way out. You figure it out and hip-hop back in those days was really inspiring to me. That’s why I moved to New York. I really wanted to be a part of it.

Has hip-hop jewelry evolved in noticeable ways?

In the beginning, hip-hop jewelry was just little gold chains and then big dookie ropes, but even then, it was personal through link styles. Then, you had things like name plates, which is where people really started personalizing. When the industry started to take off in the early 90s and people had more money, they really started customizing more and more. Then there were groups using their label chain as a symbol of brotherhood and community.

Fast forward to today and you’ve got people like Pharrell adding colored gemstones to a name plate. People want what nobody else has, which is such a big part of the one-upmanship of hip-hop.

What’s your favorite image in Ice Cold?

The Biggie portrait that opens one of the chapters where he’s wearing his Jesus piece, that’s probably my favorite. It’s just a beautiful portrait and I like the symbolism of what the Jesus piece means in hip-hop. It’s become this thing beyond religion. People have recreated it. Kanye did the Murakami Jesus and the Black Jesus pieces and then Lil Yachty did the Lil Yachty Jesus. That photo of Biggie is my favorite because it’s so rooted in classic hip-hop but it also symbolizes what hip-hop does best, which is take something, run with it and turn it into something better. Hip-hop has always had a culture of remixing and customizing, through sampling in the music to aerosol art on jackets. It just keeps reinventing.

The runner up is the photo of Tyler, the Creator with all his contemporary pieces. As a contemporary collector, he’s really smart and very studied, even though he would probably never admit it. He understands the history of things and knows what it means to be a collector.

This is your second book documenting hip-hop. What drives you to keep writing about it?

My mom was a librarian. In my heart of hearts, I grew up with a love of books and a love of being able to connect to history and stories through visuals. With hip-hop being a musical form, we know what it sounded like. But what did it look like? All those stories are kind of buried in these archives. I just thought books were the best way to preserve that. I just really love the idea that when we’re all gone from this earth, some kid is going to be able to dust off these books on some library shelf and be able to see and read what hip-hop was and what it went on to become. For me, it’s a little bit of a nerdy pursuit but it’s rooted in something that really is beyond all of us. @vikkitobak