Jim Evans, Also Known As TAZ, Reflects on His Jouney in Art and Creating Iconic Rock Album Covers

Words by Josh Jones

Photography by Steven Meiers Dominguez

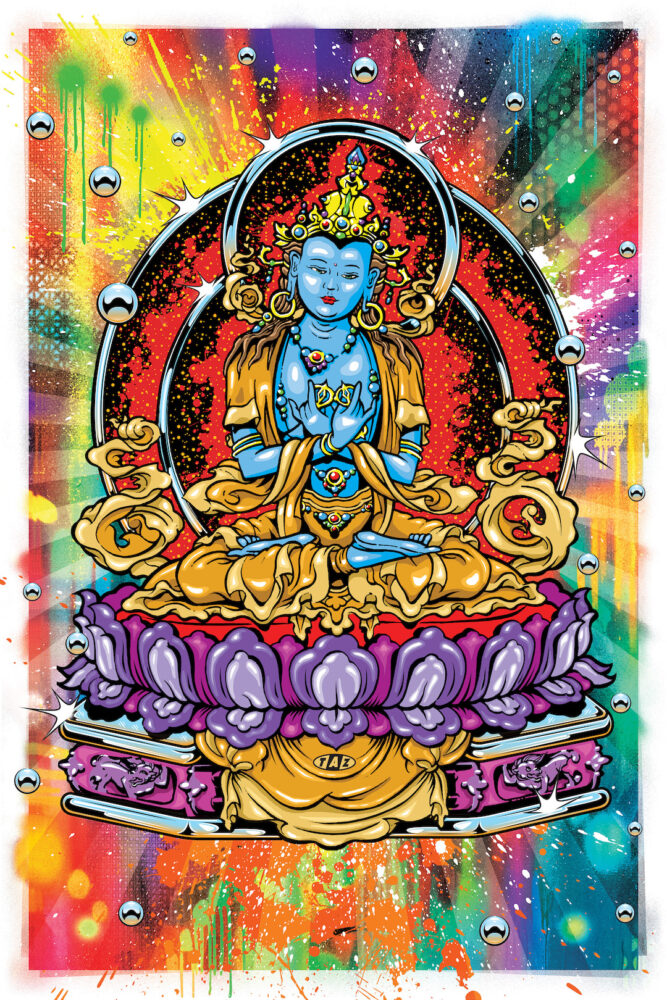

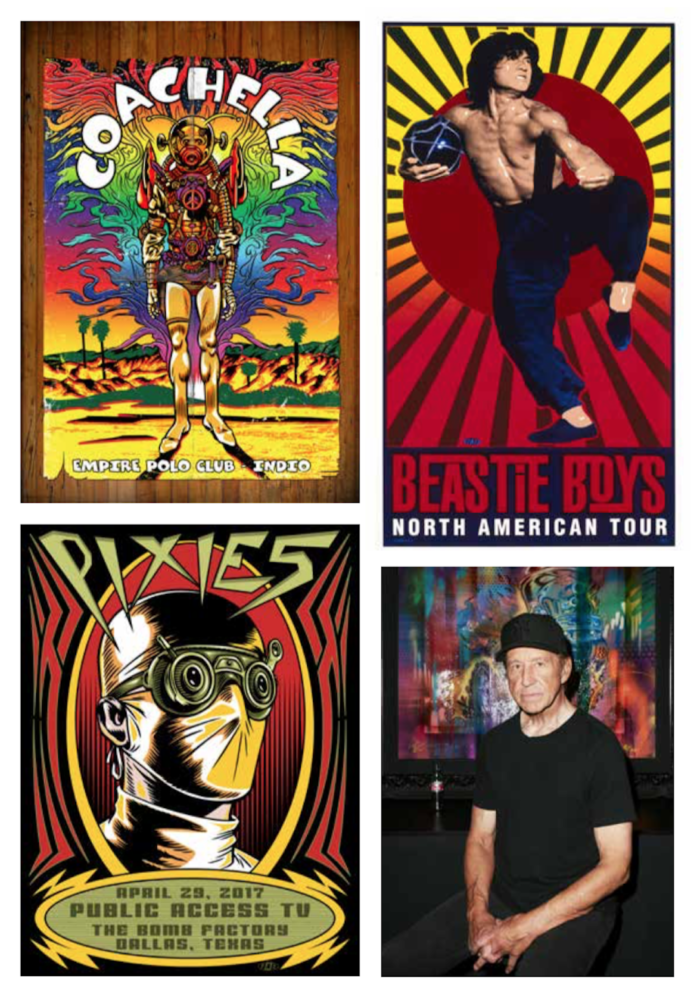

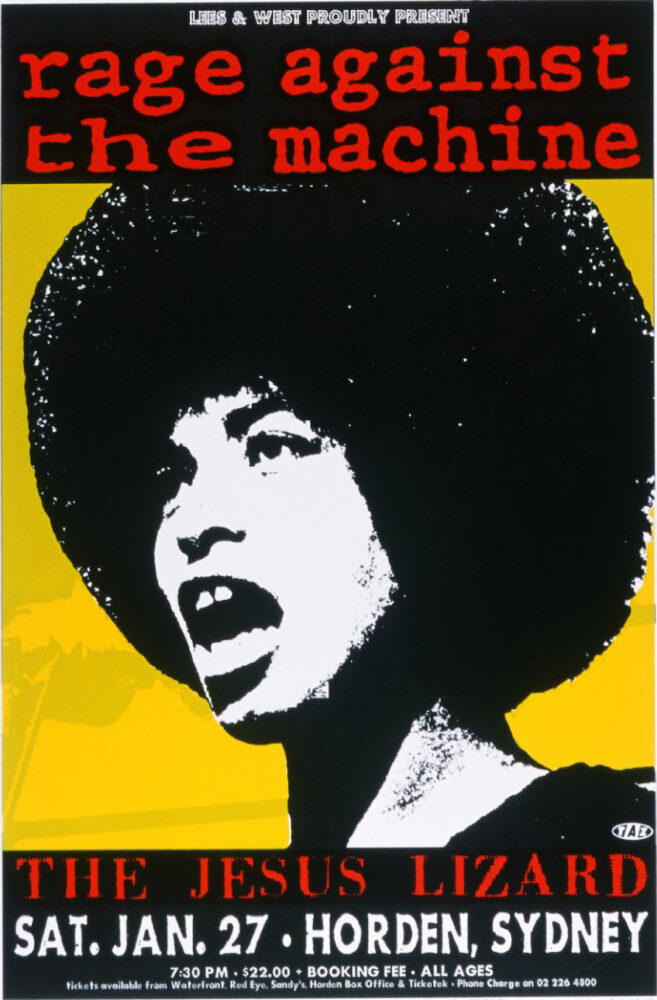

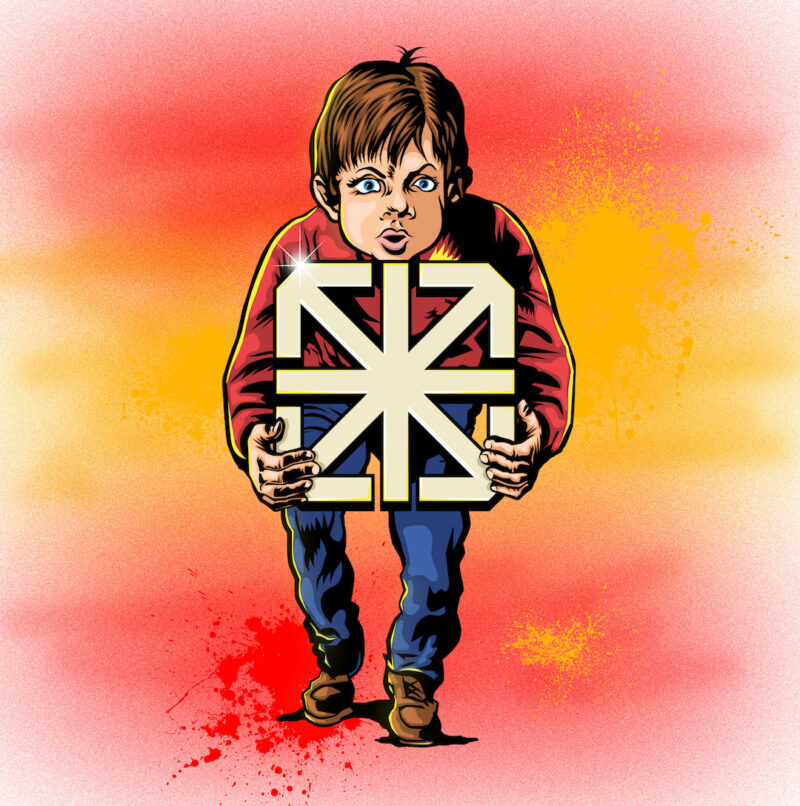

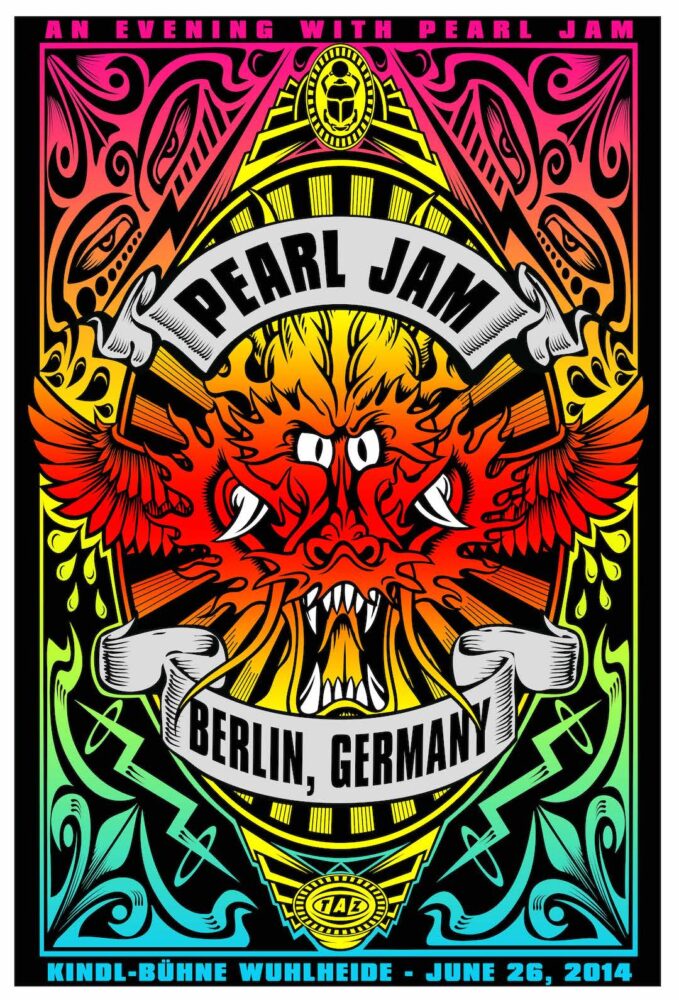

Also known as TAZ, Californian Jim Evans has been creating poster and album art for the likes of Foo Fighters, U2, Oasis, Green Day, Pearl Jam, Beastie Boys, L7, Neil Young, Beck, Aerosmith, Ramones, Rage Against the Machine, Wu Tang Clan, Metallica, Anderson .Paak and Nine Inch Nails. Cutting his teeth in the underground rock scene in San Francisco during 1967’s Summer of Love, he left being a guitarist in a rock band to concentrate on his comic books, flyers and underground art, before moving into advertising and magazine illustrations, creating movie posters and titles and, of course, working with some of the biggest rock bands on the planet.

Am I right in saying that going to art school kind of kept you from having to go to Vietnam?

Yes. It worked out well. I went into the Navy Reserve instead. So it allowed me to gain a little time to join a reserve unit which was kind of my goal. You know, I was 1A and I was playing in a band and surfing and just relaxing. And then the draft came up and my girlfriend at the time thought that I had some skill as an artist. So she went to the art teacher at the junior college we were at and she said, “you know, you should take a look at Jim’s stuff and maybe get him into an art school.” So he actually did. He had me put together a portfolio and got me accepted into what was known as Chouinard [Art Institute] at that time and is CalArts now—California Institute of the Arts—but it worked out well. So it gave me enough time to get into a reserve unit. I mean, I still had to serve my time on a ship and you know, yeah, being in the Navy. Futura was in the Navy as well.

Imagine you two on the same boat.

That would be weird, right? So it worked out well. I mean, it forced me to move up to Los Angeles and it got things going for me. I met a lot of people up here. And they helped, you know, kick my career into gear. I met Ron Cobb, I met Rick Griffin. And both of them were very influential at the time, and they both helped me quite a bit and moved my career forward.

I like the story of you just drawing in a diner and Ron Cobb walked past and was like, “I kinda like your stuff.”

I mean, that’s like a weird movie isn’t it? That’s exactly what actually happened. I was working in Westwood for a magazine. I was a photographer and layout artist. I was the photographer because I had shoulder length hair at the time. And I was the house hippie. For instance, there would be like some student riot going on or the Black Panthers were setting up something and I was the guy that could actually just grab my camera and walk in there. They set me up with a press pass and I would just go into the middle of these things and shoot pictures for them. And then the [Los Angeles Times] would buy them and the magazine would pay for them. So it was kind of a cool deal for me. One lunchtime I was down in this little restaurant drawing cartoons and Ron Cobb walked by the table. He said, “hey, can you do more of those?” I said, “yeah, I do them all day long. I’m eating a sandwich doing them.” And he said, “well, we’re starting this press, that’s going to be syndicated to underground newspapers all across the country.” I said that’d be cool. So I started doing cartoons for him, which was a huge break for me, because I was literally nobody and suddenly I had my cartoons in places like the Detroit Free Press, New York Free Press, Los Angeles Free Press. Suddenly, my cartoons were everywhere. That was a huge jump.

You called Summer of Love “the new age of everything.” What did you mean by that?

I was brought up on military bases so all I knew really was being a tough guy, like death before dishonor. And then when the youth explosion started happening it really wasn’t bought into immediately but when it started, it just exploded in every direction. So you had art and music together, right, and you had all sorts of creativity. It was a democracy of pop culture that had never really happened before, and I don’t think has really exactly happened since. For a kid like me, everywhere I looked I saw something that told me, I could go there and do that. And as I jumped into it I realized that, for some reason, I was built for this kind of a thing. I had the mindset to jump into it and be one of those guys, so it kind of came easy. I was excited by it because it was going off in every direction. I went to the Monterey Pop Festival and after that, we went to San Francisco and I hung out at Haight-Ashbury in the Summer of Love and saw Jimi Hendrix on stage there. At the same time the movie [Michelangelo Antonioni’s] Blow-Up opened—the one about Swinging London and all those models and that photography. It seemed like creative paradise was everywhere you looked. Having a bunch of my beatnik friends take me up to the canyon in Laguna Beach and introduce me to all their old friends was like going to another planet. Seeing their record collections, their hair and the drugs they took. It was like, my eyes, were just wide.

You seem to have been constantly working since high school. Have there been barren periods or bleak times where shit just wasn’t working for you?

There absolutely hasn’t. I’d be one of the few people that never really had that happen to me. I mean if you look at my work, I’d say you can see that I’ve been kind of flexible. What I did in 1969 for the first album cover for Alice Coltrane is far different than what I do now although you can see little bits and pieces of the ideas in the approach. But at the same time, I’ve never really stuck with one particular style. I’ve always been pretty fluid. And when I went to someplace, I would just kind of adjust my style to like what was going on. Like when I moved to Hawaii, I adapted to what was going on there. And I started doing brochures for The Rolling Stones when they came in. So it was like I suddenly became like big rock artist because everybody else on the island was dropping acid and trying to be super hippie-dippie and doing flowery things. I really saw myself more as a branded rock guy. I really liked doing that kind of thing. So I stood out from everyone else — it wasn’t like I had a lot of competition. So I got all the work. I would say that I worked probably nonstop from the time I was 19 to now.

How have you kept discipline to not just go surf?

That’s a good question. I consider myself kind of a lazy guy but I’m actually not very lazy. The one thing that drove my discipline was the fact that I was excited about the work that I was getting. And I felt like each piece was super important for some strange reason. I felt like when I got something, I wanted to make it iconic. So I really got into that. I mean, I actually worked myself to death. I played in a rock band all through high school and my friends would come over and play. I’d be working on something, they’d go, “well, that looks pretty cool.” But I never really wanted to admit to them how much work I put into it. I’d be like “let’s play, I can get back to that later.” And in my mind, I’m going, it takes me so long to do this art. At the same time, it was satisfying so I never got lazy. I ended up getting tired because there was so much work but I was pretty disciplined in getting stuff done. When somebody would give me something, I felt responsible to give them something really, really good back.

When someone looks at your work, isn’t it sort of like you’re in control of their view so to speak?

I would say that I’m obsessed with that. I got into Eastern religion and philosophy really early on. And I found the collective unconscious—in terms of religion, philosophy and things like that—was basically a guidepost to like what I needed to do in order to do what you just described. I read Carl Jung’s Man And His Symbols and I realized that if I paid attention, if I just tuned into basically a subconscious radio station and know pretty much what everybody’s thinking then as I construct my pieces, I use the right colors and I use the right shapes. I would say that manipulating the attention of the viewer is pretty much what I’ve done in every piece I’ve ever done. It’s all I think about.

I guess that stands you in good stead with more commercial creative as well.

The advertising stuff wasn’t something that I would say I wanted to do at first. But then the amount of money being paid for it and the attraction to the sort of propaganda manipulation on a very large scale by a huge corporation kind of fascinated me too. So I was able to carry what you just described over into that and I was just kind of made for it. I mean, it’s kind of the way I think. Yeah, I would say I definitely manipulate the viewer.

Is it possible to sell out as an artist?

I don’t think it is. Gallery artists would say they don’t sell out because they do pure art and they hang in a gallery but at the same time they have to have a viewing audience. And they’re doing something that the viewing audience likes. I mean some people might try to really piss people off but then that’s like a whole other strategy. I think we’re basically the result of a series of strategies so I think that art by its very nature, if you’re a professional artist, you are an artist for hire. And you reach the highest echelon of basically either manipulating people’s feelings or emotions or their consumer drives or their ability to want to go see a rock concert or just to walk around in a gallery and hold a glass of wine and go like, “oh, that would look really beautiful on my wall” or, “that’s so offensive, why did he do that?” With artists I don’t think there’s a way to sell out.

You described your work on the Ill Communication album artwork as the most complete collaboration you’ve done. How so?

The idea first started with Mike D coming over, and he wanted some lettering style. He said, “I know you do a lot of hand lettering. Could you do that architectural style that kids do in high school?” I could do the entire alphabet with my eyes closed so I lettered out the entire alphabet in that style. All lines and everything just like I would have done in high school. And he goes, “okay, that’s gonna be our lettering style.” At that time, my son was beginning to work on a computer and he had a program called Fontographer and so was able to scan it in and actually create an alphabet. Previously, I would have had to hand letter this entire album which I did for other albums. And then he started doing the layout. The collaboration was in the sense that we just did the thing over and over and over again. I mean we basically allowed it to evolve through whatever they wanted to do. I think the album cover changed fifty times until it finally ended up with that photo they used but they kept the lettering style. If you open up the album, you can see the lettering is basically an alphabet throughout the entire album. The fact that my son was working on a computer was the only thing that really made it possible for them to make the level of changes. At the end, we had a gigantic hard drive. We couldn’t even take the files and transfer them over to give them to print. We just gave them the hard drive. We took it over to Capitol Records and said, “here’s the whole thing, just do what you need to do.”

Was there really so much discussion about it?

Yeah, there were a lot of chats. I hung out with the band a lot at that time. I went on a golfing trip with them. I went on a snowboard trip with their manager. I mean I actually met the Dalai Lama with the Beastie Boys. We became really good friends so it was an easy job. They know exactly what they want and they don’t mess around. They keep changing but at the same time they really have a pretty precise idea in mind. I wanted to give them everything they need for it because I thought this was really going to be an historic album.

What other pieces of yours have good stories?

The Shogun Assassin poster I did in 1978 was kind of a pretty cool one. Because I mean the Wu Tang Clan jumped on that one, and it’s in Kill Bill. It’s one of Quentin Tarantino’s favorite films. At the time a producer named David Weisman had this idea to basically get some samurai films and recut them like an American film. He asked me my favorite samurai movie. At the time, I was a huge samurai fan. I took my kids to see this movie called Baby Cart [at the River Styx] so I said, “well, there’s one and it’s showing in this local Japanese theatre. It’s about this guy who walks around and he’s got a kid in the baby cart. And they kill ninjas. And it’s really cool.” So he bought the rights of that whole thing and recut it and re-edited it and added a soundtrack. I did the poster. I did the titles and all kinds of things for it. So that was an interesting project. I would also say the Neil Young album cover was pretty cool, because that was a poster for Rust Never Sleeps. And that came through the same guy; David Weisman, as he was hanging out with Neil Young, I guess. They were working on a project and he said, “you know, Neil Young’s got a movie and we need a poster for it,” so I said I could do it. One day, there’s a knock on the door, and I open it and this guy says, “oh hi, I’m Neil Young.” I was like “hi, I’m Jim Evans.” He comes in and we start talking about this thing. We put it all together and it’s pretty historic. On that one I also did the titles as well. In both cases I did the titles on pieces of acetate where I painted the titles actually coming in on layers of acetate. Then they photographed it and created the sequence that you see in the movie. In both those movies, I actually did not only the title of the film on the poster but I turned that title into the title that shows up on the screen. I think with Rust Never Sleeps I did like 70 pieces of acetate.

What do you think about imitation? Is it the sincerest form of flattery or the sincerest form of copying?

I think as an artist or musician it’s really hard not to imitate because you’re influenced by so much. I would say that my approach hasn’t been imitated particularly but it certainly has been informed by literally everything I’ve seen. All the comic books I read as a kid, Mad magazine, science fiction movies, big Hollywood blockbusters, on and on. All the famous designers, Saul Bass, Paul Rand, anyone like that. Andy Warhol… For me, the hardest thing has been to be near another artist that I admired. Especially when I was younger. For me it’s really easy to imitate. I could be like a forger becausenI‘m able to sort of ascertain what’s going on in a piece and like how it’s done. I feel I can imitate rhythms. So it’s been hard for me not to be overly influenced by someone I really admired; someone that had a really powerful style. I think like, “wow, that really solves all the problems.” Because as an artist you’re always trying to solve problems. You’re trying to get to the ultimate image right? You’re trying to solve whatever problem it is to get you that image. So if you’re with another artist that has a vision that actually brings that forefront and you’re like, “wow, if I just took that, what he just did, and I could do that myself.” A lot of times I’ve actually gotten away from people because I didn’t want to be near their influence. I get overwhelmed by it. Is it the sincerest form of flattery? I would say that there’s blatant imitation and then there’s influence. I would say most famous artists have been influenced. I mean the amount of people that have been either influenced or stolen, doing Andy Warhol takeoffs… so it just doesn’t go away.

Does working with newer artists like Anderson .Paak keep you fresh?

I’m kind of honored that someone like him would come to me after all this time and see me as someone who could actually interpret what he wants. It’s kind of surprising because you think you’ve maybe kind of run out of steam. Maybe I haven’t. But at the same time when younger groups or cutting edge groups come to me for some- thing, I try really hard to make it cutting edge. I think as an artist, it’s important not to be the result of everything you’ve become. That’s why I started doing the TAZ stuff, because I was tired of being Jim Evans. It was like I’d perfected Jim Evans and all the styles that he could do to the point where all I could do was be a more perfect version of myself. Which is not really the goal of art. I mean you really want to go back to where you started. So when I started the TAZ stuff with the alternative rock posters, that was actually pretty cool. Because I basically eliminated all the years of learning that I had done and went back to my high school notebooks. I put in hot rods, skulls, girls, weird things, people with guns and things like that. So I tried to eliminate every- thing and return to a childhood where I didn’t have anything at stake. Where I just sat down and I would draw whatever hot rod I felt like drawing, with smoke coming out of it and things like that. And it actually worked. The TAZ thing, even with the Beastie Boys, was almost a giant experiment on my part to see if I could remove all my previous influences and start from scratch. Back to where I was with underground comic books when I had fresh eyes. There was nothing at stake. It was just: try as hard as you can to come up with something really cool. And it kind of worked.

What have been your most enjoyable projects?

Jeez that’s a really hard one. I enjoyed working with the guy you featured in a previous issue, RISK. I enjoyed that collaboration and engaging in the graffiti world. I think that some of the graffiti guys see my posters as being influential in the way that they saw comic artists like Vaughn Bodē being influential. The fact that I’m still working and can actually join in and do these things kind of sets me apart from other guys. I think a lot of other guys kind of get old and tired. I mean it’s like a rock band. Why do some of the great rock bands come up with so many hit records up to 1974? They’re still on the road and they haven’t had a hit record in four decades. What happens? Does your creativity just run out? You should be able to come up with something good right? If you’re the greatest rock band in the world. I mean when the Rolling Stones play basically they’re playing songs that are fifty years old. Another weird thing about pop culture is the fact that if I go to some supermarkets and I’m listening to the store music in the background, it’s The Rolling Stones, The Beatles— music that’s fifty years old. This would be akin to me as a teenager listening to the hottest record of 1912. It doesn’t make any sense. The amount of distance now that pop culture can stretch and the acceptance of older bands, either pays tribute to the ubiquity of that sound, and the fact that people can’t get out from under it, or the fact that nothing new has come out to actually supersede it. You’ve got to come to one conclusion or another, right? Because when I was a kid, nobody was listening to music from 1910 or 1912.

Finally, who would you want doing the cover of Jim Evans’ autobiography?

Wow, who’d I get to do it? That’s a tricky question. Maybe Futura. I would say he’s one of the most influential artists right now, just because of the trajectory of his career. The approach he’s taken and purity of his work just seems really right. It seems like he took that whole graffiti thing and he really made it into real paintings. The philosophy of his approach has always been really solid. It just seems like really strong creativity.

@jimevanstaz_official