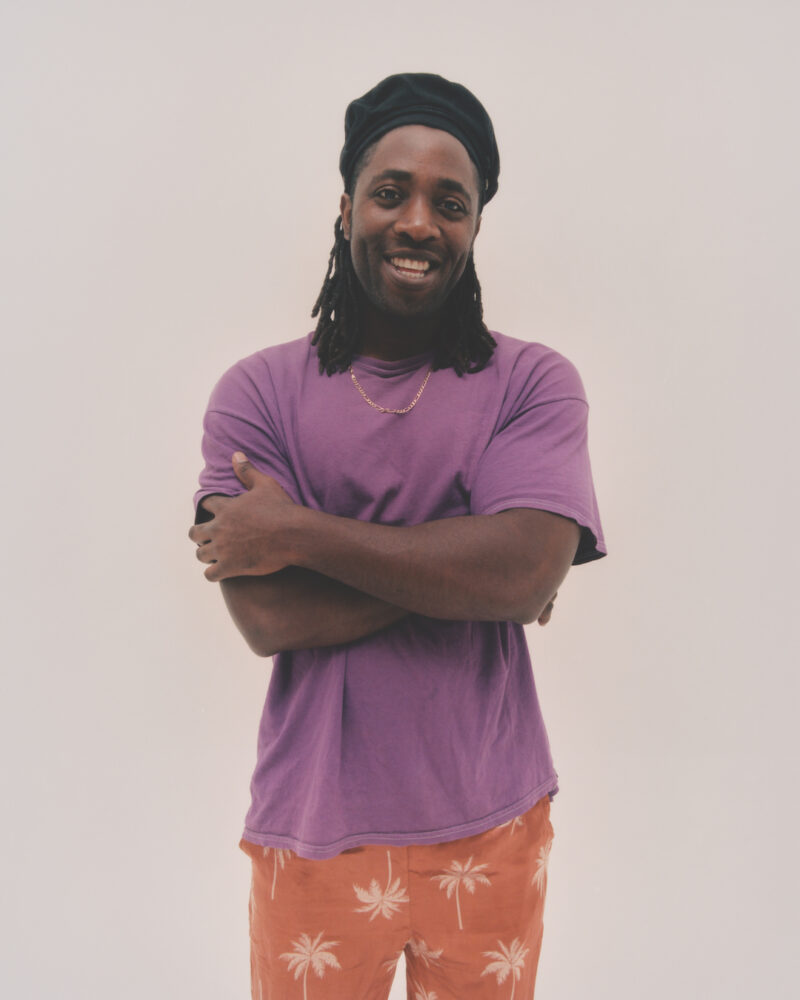

Kele Okereke of Indie Punk Group Bloc Party Reflects on the early 2000s London Music Scene and their Two-Decade Evolution

WORDS by ALEX FRANK

PHOTOGRAPHY by ALEX DE MORA

Sometimes, in an age of endless Spotify playlists crafted to blend seamlessly into the atmosphere of your life, it can feel like all the hard edges have been smoothed out of music in favor of something chiller, softer, colder and more easily pleasant as it streams out of your silky wireless speaker. Bloc Party, the jumpy British indie band that’s been making music now for two decades, is the countermeasure. “We grew up listening to music that had edges and we wanted to have edges,” says Kele Okereke, the lead singer and songwriter as we video chat between New York and his home in south London. “That’s always been the back of our thought processes: how can we do it, but make it ugly? We’re not happy unless it’s slightly wonky.”

Bloc Party came to prominence at a very different time, in the mid-2000s, when a burst of post-punk BLenergy was percolating through the industry in the the pre-gentrified East Village. It’s starting point was noir-esque: tracks that are tales of woe inspired by the rougher sides of sexuality and the depressing, post-Brexit-Boris-Johnson era of UK politics. “The core running through the record is people abusing their power,” says Okereke. “What does it mean when the people that represent you don’t have any integrity, when their only goal is power? Ruthless ambition, ruth- less domination. What happens when you stop treating people as humans? What happens when you’re so single-minded that you lose your humanity?”

A start-to-finish listen to Alpha Games can feel a bit like binge watching HBO’s Succession—sinisterly entertaining but a bit disheartening too. Seductive on the outside, rotten on the inside. Take the high-strung first single “Traps,” a track in which Okereke envisions a romantic conquest as Bambi…headed for a trap. “It can be read as a come-to-bed, seduction song but for me, it goes a little bit deeper. To me, it’s dark. To me, it’s about an abuse. It’s about taking advantage of someone,” he says. On “Day Drinker,” a track he says epitomizes the album’s themes of domination and sub- mission, Okereke sings about a dramatic and ultimately doomed clash within a family. “[That song] is about the rivalry that exists between two brothers,” he explains. “The younger brother has been successful in life but the older brother has not. He has become a waster. Know- ing that he can no longer compete with his younger brother’s successes, he has given up the fight.”

In this way, Alpha Games is the culmination of everything the band has been exploring since the very beginning. Their breakthrough single in 2005, the timelessly thrilling “Banquet,” was itself something of a fiery garage rock romp. “It has this — I don’t know — tribal, dark, weird, sexual energy. It always makes me think of Adam and the Ants,” Okereke says. “I always imagine strippers grinding on poles to that song. It just has something insistent and sexy and urgent and a little bit dangerous. That’s what that song feels like to me. It feels a little bit dangerous.”

Before being a rock n roll master of the dark arts, Okereke had a relatively uneventful childhood. “I grew up in East London. An older sister, two parents that worked hard. We didn’t have a lot but they made sure that we didn’t go without,” he remembers. “I think the only thing I can really remember is I felt like I spent a lot of time waiting for a point where things were going to be different. I always knew that I was different and I was going to go somewhere else. I always had that sense from an early age.”

Okereke, like many queer people, doesn’t feel like his life truly began until he got out of his childhood home. “I don’t really go back and think too much about the life that I had before I left home because I wasn’t out at home. I felt I never really could be,” he explains. “I can’t really think too much about those years. I feel I was a different person.” Okereke did spend his child- hood years making himself into a musician, though. “My earliest memory of making music was that my sister had an acoustic guitar in her room when she was in her early teens. When she was out, I’d go up to her room, steal her guitar and play it,” he says. “I taught myself dangerous chords. I started writing songs. I wasn’t really interested in working out other people’s songs. It was always really about expressing myself.”

In high school, he met now-bandmate Russell Lissack and, a few years later, they decided to form the band that would eventually become Bloc Party. By 2005, they had a debut album Silent Alarm—which featured what is still their biggest hit “Banquet”—and it took off like wildfire. They were heady days in the UK music scene: similarly-minded bands like Franz Ferdinand were helping kickstart the same rock wave that Bloc Party would surf and Amy Winehouse was a critical darling and tabloid fixture for her riveting and rebellious R&B. In fact, Okereke met Winehouse at a night- club in those early days. She told him that she fancied him but gave it up when she realized he was gay. He went on to witness what the spotlight and a cutthroat music industry can do to performers. “It became a sport for the British press, following her around and hounding her. She’d been to rehab and she’d just come out. She was so frail. A shell of a person,” he remembers. “Earlier in her career, she seemed full of life and she seemed like she was a ghost towards the end.”

After the triumph of “Banquet,” there were pressures to keep the hit parade up. “When you do start achieving success, suddenly the voices around you become louder telling you what you can and can’t do,” he says. “It’s very easy to listen to the people telling you to do this, because if you do this, it means you’ll be able to achieve this and make more money. You have to have a sense of determination.” He says he was lucky to have a management team that shielded them from the sharks and encouraged the band to focus on the craft. “It meant that we were allowed to just find out what it is that we wanted to do. I always think it’s so sad that so much raw talent can get perverted or turned into something else,” he says. Okereke deepened his commitment to songwriting. “To have this outlet of being able to express myself, it’s not just a job, it’s part of who I am,” he says. “I have to treat my art with respect.”

In 2007, the band released their second album, A Week- end in the City, a mature if somber record in which Okereke lyrically explores everything from suicide to capitalist excess. The song “Where Is Home?” concerns the death of Christopher Alaneme; a black teenager who was killed in 2006 in a racist attack. With its attention to injustice, the song is something of a presage of where music has gone since: artists are now practically expected to chime in on sociopolitical issues in a way they just weren’t fifteen years ago. “I like there is more language around understanding other people’s perspectives in life,” he says. “I remember after George Floyd, that whole year, overhearing so many different discussions about race. Just casually, people on the street or television shows. It felt like the language around diversity was changing.”

Which isn’t to say that Okereke is all serious. On Alpha Games, there’s “The Girls Are Fighting,” a song that is a cheeky ode to girl-on-girl aggression. “Growing up here in the UK and going to clubs and being around drunk people, I’ve seen a few girls fighting. Fighting over lovers, or boys that have been selling them dreams,” he says. “I’ve always been fascinated with the moment that things become violent. Things become physical. That moment where someone’s blood boils enough that they reach over and throw a drink in someone’s face. It’s electric that moment because you see people’s true characters at that time. I’ve always thought that was a very frightening energy. Scorned female energy.”

Ultimately, through all the years, what’s mattered most to Okereke is just that he gets to do this, song after song, album after album, a career spent exploring music no matter the cultural or sonic climate. During the pandemic, he’s been able to reflect on a life spent in sound, realizing that whatever is happening in the world around him, for the last 20 years, his mission has largely remained the same. “I was still able to do the thing that I loved,” he says of living in lockdown. “I was still able to wake up every day and think about music and work on music and eventually record a record.” The music might be dark and even a little, “wonky,” but Okereke has remained endlessly, relentlessly inspired through it all. “I’m constantly reminded,” he says, “that the life that I have is a blessed life.”

@thisisblocparty