Kings of New York: A Flashback to the Epicenter of 80s and 90s Skate Culture

Words by Cullen G. Poythress

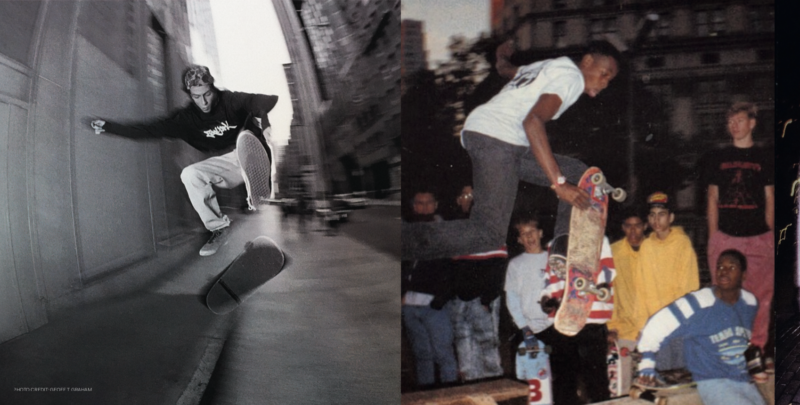

Photographs by Archive of Eli Morgan Gesner

Camcorders, instamatics, 35mms, they were all there capturing sessions on the skate ramps and mics of NYC streets. By now media of the era has become an art form itself. One that filmmaker Jeremy Elkins has curated for viewers in his latest documentary, All The Streets Are Silent: The Convergence of Hip Hop and Skateboarding. The film presents a supernova array of visual subculture as it happened on the Brooklyn Banks (RIP) and West Village stoops of the 80s and 90s. Elkins has plumbed archival footage with the eye of one who was there. What we wit- ness are racial presumptions falling apart in favor of the common language of the streets, and the birth of a subculture no one predicted. Cullen G. Poythress tells us more of the story.

As a skateboarder growing up in Atlanta during the early 90s, the energy coming out of New York was every- thing. Sure we had our own thing happening down South, but back then there was no YouTube, Instagram or Spotify— no internet. Unless you were showing up at downtown spots, trading tapes, swapping mags and talking shit there was no real way to know what was happening. All we knew outside of our own scene was what was being exported on VHS tapes from California skate videos featuring skaters we’d never heard of, skating spots we’d probably never go to, set to music that wasn’t always relatable. But when East Coast skate videos like Eastern Exposure 1 [1993] and Zoo York Mix Tape [1997] started rolling out there was an instant feeling of recognition. It was familiar. It was resonant. It was us. New York skaters gave us a voice, an attitude and a sort of hip hop-adjacent identity we could call our own—a kind of raw, invincible street style a world apart from the West Coast. It wasn’t skateparks. It was street. It wasn’t about tech. It was about going fast, splitting lanes and ruling the metropolis—smashing up walls, blasting through ledges and looking stylish as fuck while doing it—big wheels, Shell Toes and camo fatigues matched with the hard beats and lyrics of New York rap. Skateboarding was cool but skateboarding mixed with hip hop was untouchable.

The American story is rife with tales untold. It’s a memoir full of scantily whispered names and seemingly innocuous events few will ever know of unless they were there. It’s only when examined through the lens of modernity do these overlooked threads of history begin to reveal their meaning and significance.

It’s this presumption that underscores the core of the film. One part anthropologist, one part historian and one part skateboarder, Elkin delivers an exposé into the origins of what might be precariously defined as street culture. Nothing in NYC happens in a vacuum—and it was this diverse, auspiciously connected cityscape Elkin proposes helped catalyze what would become one of the most powerful cultural movements in contemporary American history.

It’s a tale of outlaws, outcasts, vandals, creatives, op- portunists and the relentless energy of youth. It’s equally a story of innocence, serendipity and the beautiful chaos of a bygone New York now mythic in the annals of America’s countercultural past. As the film’s narrator Eli Gesner explains, the Lower East Side of Manhattan during the late 80s and early 90s was a much different environment—a neighborhood full of drugs, crime and low income apartments. “Having an a/c was a luxury back then,” recalls Gesner. “Imagine everyone in the city spilling out onto the streets during the summer to escape the heat. People were literally just hanging out on the streets talking, play- ing, leaning on cars and meeting each other. That’s just what people did back then.” Rampant poverty and a sub- sequent lack of air conditioning might seem like a trivial detail, but in Gesner’s experience it was just one of many environmental pressures that enabled a transformative blending of inner city cultures. “I’ve always compared what was happening in the streets back then to Café Society in Paris or The Harlem Renaissance,” he continues. “It was the opposite of today’s gentrification.”

Creating an establishment that catered to the Lower East Side’s organic confluence was just what Ulli Rimkus had in mind in 1989 when she opened the doors of Max Fish—a Ludlow Street art bar and eventual de facto water- ing hole for the city’s young and inspired. “I moved to the Lower East Side in ‘79,” she says. “The neighborhood was so full of junkies and drug dealers that the cabs didn’t even want to drive down there during those days but at the same time nobody bothered you there.” The film captures the essence of the world Rimkus describes as it opens with archival footage of teenagers carelessly set- ting off fireworks in the streets—suggesting, in part, that it was the lawless concrete of the Lower East Side and its overlapping social scenes that would set the stage for an explosion of youth-driven creativity and rebellion.

Away from the avant garde personalities of Max Fish were places where skaters, artists, musicians, photographers and other creative types cohabited. Among these urban petri dishes were the brick embankment under the east side of the Brooklyn Bridge unofficially known as the “Brooklyn Banks,” (sadly just torn down by the city during lockdown), a multi-level nightclub called Club Mars and the lease line of a newly opened skate shop on Lafayette Street called Supreme. “The Banks get a lot of play in the documentary,” explains Gesner.

“But that’s mostly because we brought video cameras there to film skating. In reality, Washington Square Park held an almost bigger role in socialization. You’d go there to meet up with other skaters but there were also girls there, guys working in the hip hop world and drug dealers. There was lots of intermingling going on.”

The retail floors and sidewalks in front of Supreme were another location. Opened just blocks away from Broadway’s bustling shopping district, the store quickly became a meet up spot for local skaters and a headquarters for its skate team and employees. Original Supreme team rider Peter Bici witnessed the energy and camaraderie the shop cultivated first hand, recalling it as a vital epicenter for the New York skateboard community. “Having the shop as our home base was very important because we had no other skateboard shops around,” he says. “It was a very special place for us and something we all needed. We used it as a skate shop, a home, a hangout and a clubhouse.”

Supreme was also a place that helped usher in a new and unique identity for New York skaters amid the mostly California-dominated industry of the day. “The difference between West Coast and East Coast was very particular, especially in style,” says Bici of the emerging East Coast skate style he helped define. “Growing up in New York City builds a certain type of character,” he continues. “It’s a type of grit and a raw persona that you get from your surroundings. That transcended into our skateboarding styles—and the shop created a family and a bond we all connected with and adored.”

Skateboard companies also began to emerge from the New York scene using a similar blueprint to what surf, skate and streetwear brands had been doing in California during the previous decade. Gesner, who co-founded the Zoo York skateboard company in 1993, minted the brand in the image of the empire state and the many cultural fusions it epitomized—draw- ing inspiration from graffiti, hip hop and a roster of pro skateboarders representing a new style and approach to street skating that was unmistakably East Coast. “I got into skateboarding because I was a graffiti writer,” Gesner says in reference to Zoo York, the original logo of which bears the marker-drawn handstyle emblematic of 90s graffiti. “But the Soul Artists of Zoo York [skate crew] were doing this stuff in the 70s before I was ever skateboarding or writing graffiti,” he continues, giving credit to some of the city’s pioneering writers including Haze, Zephyr, Revolt, Futura, Andy Kessler and Puppet Head.

The Zoo York namesake and visual identity were just a part of the subcultural elements the brand captured. Music, specifically a new breed of hip hop emerging from the city’s downtown club circuit would become the brand’s soundtrack—beats and rhymes that would end up scoring one of the most influential East Coast skate videos of the decade, Zoo York Mix Tape. Its principal filmmaker R.B. Umali says the film was a powerful force in helping to export the style, sounds and look of New York City to the world. “Hip hop and skateboarding complimented each other perfectly,” says Umali. “Eli was friends with Stretch [Armstrong] and Bobbito [Garcia], everybody knew Harold [Hunter] and Vinny Ponte was a DJ who was down with everybody at Fat Beats [record store]. It was a small community and we all looked out for one another. It really affected the way we talked, dressed and skated.”

Opened in a Lower East Side basement in 1994, Fat Beats was another important brand name within the 90s hip hop lexicon. Founded as both a record label and retailer, Fat Beats became a mecca for local hip hop heads for its diverse vinyl offerings and spontaneous in-store performances. Original Zoo York pro and DJ Vinny Ponte was an employee during the store’s early days—a position that would lead him to cross paths with DJs like Stretch Armstrong and Roc Raida and eventually land him on international tours with Big L, the legendary Harlem lyricist. Although Ponte remembers skateboarders and rappers as often having distinctively different circles, he says the two groups shared a mutual fascination and respect for one another. “We were out in the streets and they were out in the streets,” says Ponte. “They’d be looking at us like, “yo, what the fuck are you guys doing” and we’d be looking at them like, “yo, we love your music.” They weren’t trying to jump on skateboards and we weren’t trying to jump on the mic but we recognized each other.”

If it was Max Fish, the Brooklyn Banks and Supreme that brought the skaters together, it was Club Mars– as highlighted in the film– that offered a communal musical playground for the full spectrum of the down- town scene. Blending graffiti writers and skateboarders with MCs, DJs, actors, models, promoters and other impresarios of New York nightlife. Opened by Yuki Watanabe in 1989, Club Mars became a breeding ground for new talent and its multiple floors and stages served as the launch pad for hip hop’s soon-to-be global revolution. Cultural critic and curator, Carlo McCormick, worked as the club’s doorman during its heyday and bore witness to a staggering array of would be stars perform in their infancy including the likes of JAY-Z, Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, A Tribe Called Quest, Black Sheep, Moby, Jungle Brothers, Busta Rhymes, Gang Starr, Kool DJ Red Alert and many others.

In hindsight, McCormick points to two specific factors that made the club and the artists and clien- tele it catered to so important to the evolution of the New York music scene. One aspect he points to was its erratic, diverse and often unexpected approach to music programming that set it apart from what other, more musically conservative clubs were promoting at the time. “You could get away with a lot in there,” McCormick says, laughing at the wild and whimsi- cal performance bills and DJ sets the club frequently offered. “On a given night you could find heavy metal next to rap next to lounge music.”

Another important facet of Club Mars was that it offered up-and-coming hip hop artists a place to per- form to downtown crowds—an opportunity McCormick says was surprisingly rare at the time. “There was so much talent and creativity in that world [hip hop], but those guys always struggled with finding opportunities to play,” he says. “They [the artists] were all really ambi- tious, but hip hop had gotten such a bad reputation because a lot of the audiences it attracted were really misbehaved. That made it really hard for those guys to find cool places to perform.”

Club Mars and its tolerance for musical experimentation offered artists across genres a place to play and in turn attracted a new type of crowd who would embody the look and attitude associated with its dance floors. “In any crowded club there’s a million stories,” says McCormick. “I remember cool kids coming into Mars representing a different demographic and bring- ing in a new energy. You wanted a good mix like that. You wanted the junkies next to the models and the movie stars. As club people we were just trying to express the sensibilities of what the kids were doing.”

As All The Streets Are Silent tactfully illustrates, the youth culture of today in all its modern iterations frequently harkens back to this formative decade—with vestiges of its influence hiding in plain sight for those keen enough to recognize it. The weekly lines down the blocks of Supreme locations around the world, street skateboarding’s adoption by the IOC as an official Olympic sport, the global ubiquity of hip hop and the mass produced street art prints that adorn the walls of millennial apartments are all breadcrumbs leading back to those who dominated the streets of 90s New York. For the architects of the movement’s genesis, it would have been nearly impossible to imagine the level of popularity, profit and corporate interest the culture enjoys today—often creating a kind of cognitive dissonance among those who built it— a wanting to protect it while simultaneously wanting to see it grow. “It’s com- plicated,” says McCormick. “When people get older they want to try to own something which they can’t own anymore. People are so precious about their moments of engagement, but you can’t own hip hop and you can’t own skateboarding.”

Ian Michna is the founding editor at New York-based Jenkem Magazine —an independent online outlet publishing news, interviews and critiques on modern skateboarding. As an editorial voice for the new generation of New York skaters, Michna understands the sometimes protective sentiment held by the culture’s forebears but also feels there’s plenty of room for the next generation to reinvent its future. “It’s always beneficial to know your roots, especially in a subculture as rich as skateboarding,” he says, but that doesn’t mean you have to play within the confines of history or be restricted by it.” Michna says he’s inspired by the approach and inclusiveness the city’s young skaters are bringing to the table. “The renegade creative spirit of skateboarding is thriving in New York,” he says. “Each generation has something new and special to show and it’s never been more diverse, odd, playful and empowering than it is right now.”

If there’s one thing skateboarding, hip hop, graffiti and other sacred arts of the underground have proven, it’s that they don’t need saving. Nor are they anyone’s cross to bear. By their very nature they are rebellious, clandestine and ever evolving—features that will always keep their core rituals just beyond the reach of the mainstream. So as the culture hurls itself into the future the only real question seems to be what new and exciting expressions are in store from the youth who control it—a youth who whether they realize it (or not) are perpetually building off the same blocks ruled by those who came before.

@allthestreetsaresilent