Portuguese Artist Vhils Discusses Creating Out of Chaos, NFTs and Further Technological Advacements in Art

Words by Doug Gillen

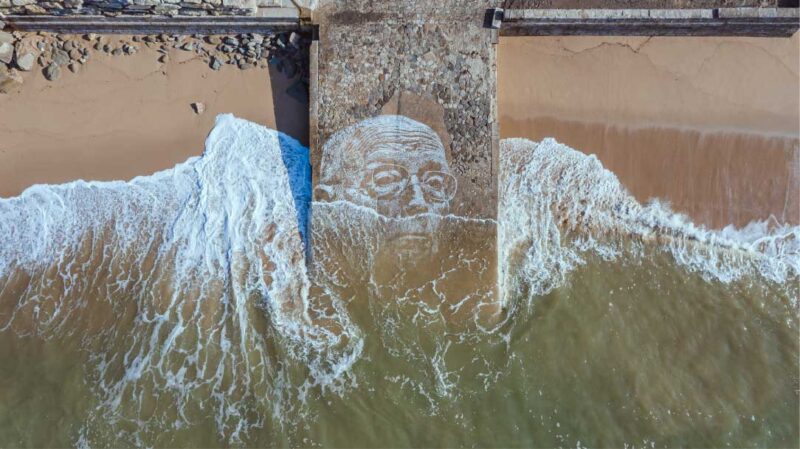

Few artists have exploded onto the mainstream art scene—literally– as has Portuguese artist Vhils aka Alexandre Manuel Dias Farto. He’s been expertly weaving his graffiti into the fabric of our cities since the 90s with a momentum that went from letterforms to portraits, spray paints to jackhammers and trainyards to museums.

In 2011, he did the “M.I.R.I.A.M” music video for Portuguese instrumental, hip- hop band Orelha Negra. The video art treated viewers to slow-motion explosions of airborne debris coming from a series of explosive charges embedded in a wall. The seeming destruction eventually resolving into a portrait of a woman. Ten years on since that first explosion, NFTs have captivated the imagination of creators around the world as a new way to make performance permanent. Speaking between the UK and Portugal, our conversation begins like all conversations of this era, with Covid.

Chaos seems to be a driving force for your work.

I mean it is but then it was very quiet while Covid was hitting so I was really focused on the studio. Now with things opening up, it’s crazy again. I’m not sure if I want the same rhythm as I did before all of this.

I think a lot of people are trying to reassess what’s changed for them during this period.

I was always moving around so I didn’t have as much time to be in the studio. This allowed me to focus on exploring new ways of creating; through the internet, through the metaverse, all of these things. I’m not trying to dramatize it. It was not easy for anyone but it allowed me to be introspective and work on things that I’d been putting away for a long time. In that sense I think it’s affecting my work and it will affect the work of a lot of people because it’s a very specific time that we are living in and previous pandemics were succeeded with really creative, explosive times.

Tell me about some of these concepts you’ve been working on. There was this perfect moment where NFTs started exploding at the same time everybody was locked down, so we were all in this digital space together.

I heard about NFTs before but I was like “what the fuck is this?” It was really in the infancy and I knew nothing about blockchain or how this could be really transformative. There are still challenges regarding energy consumption but beyond that it’s another stage. It really frees you from the classic gallery model for creating work where the outcome is physical. The work that I do in the street is usually ephemeral, demolished or destroyed in the end. For a long time I did video art as installations but let’s be honest, it wasn’t very easy to sell the works to collectors. So the fact that you can work on something where you don’t worry about whether the final result is physical– it really opens doors.

I’d sold like two or three videos before to collectors and I found [the process] awkward. I was selling a USB with the file and sending a physical certificate. All the video artists since the 70s have done that but it was a very niche group of collectors that really understood. But the provenance of those works was always a bit sketchy. What the blockchain allows you to do is create something that is verifiable from the creator to the collector. That really changes the game. That’s why I did Implosion, which was a dream for 10 years and I was able to do it and finance the whole project. It frees your creativity from the fact that you need to have something physical and for the work that I do it’s game changing.

Is this real or a flash in the pan?

At the time I really thought it was a fad. As I went down the rabbit hole of possibilities, I now feel that it’s something that is here to stay. With the traditional art world, it’s very opaque. You don’t see all the transactions; all these people trying to buy and sell. With NFTs, it’s completely transparent. You see in real time how things are doing so it’s a completely different perspective– with positives and negatives. The trick is to use it as a medium or a tool that can connect you to your community and to forget about the money part of it, because it’ll happen.

What other components of tech or the digital world are interesting you these days?

I’ve been experimenting with so much and it’s essentially what gives me the will to create. To put myself in an uncomfortable zone. Sometimes it goes wrong and that’s ok, it’s part of it. I’m really interested in capturing the moment that we’re in. By creating situations where we are more in touch, where we are always stimulated, it’s giving us a comfort but we are also forgetting about the control aspect of technology.

How do you see technology evolving as an art medium?

I’m working with programming robots that can break walls, VR and the metaverse. I’m trying to use technology as a medium of destruction that creates. I’m also work- ing with industries that were forgotten, manual labor and manufacturing– especially in Portugal– with tiles, ceramics and so on. I’m trying to blend these worlds of huge high tech to human creation but in a very brutal way. Then on the other hand, I’m working on another project which is based on this idea of being trapped in a globalized world. Looking at an honest moment of humanity where we are in touch with the world but we can’t leave our own homes. I think that’s a glimpse of a very dystopian but very possible future. In terms of our impact with travel and our impact on the environment. It’s really starting to resemble a dystopian movie. I’m trying to find my place here and bring reflection. Technology brings you [new comforts]. How much are we ready to give up in the name of our comforts?

It’s been ten years since M.I.R.I.A.M. It was your first music video and you blew up a wall. What was that experience?

I grew up in Lisbon and there were always a lot of walls. There was always a lot of decay. The whole city was forgotten and I was interested in what lay underneath. There were murals from revolutionaries, a lot of graffiti, anarchist left-wing propaganda like stencils and so on. So there were a lot of layers in the city when I was growing up. I started to do graffiti in the 90s and all of it went on top of all these layers, and the city was cleaning them. I was fairly okay at letters but I was not really pushing anything.

I remember wanting to try something different. To actually go in and extract by exposing the layers of the building or the layers of the old graffiti. During the financial crisis, I wanted to create something that was reflecting our fragile world, to show metaphorically that sometimes you just need a spark, and an explosion happens. It brings with it a new image that comes with layers from the past.

I tried to explain this to my galleries. I wanted to explode a wall and create something but nobody wanted the risk. So I ended up using my own money. After a lot of trial and error it worked. Back then the cameras were very, very expensive to rent and it was an expensive process to get it right. That project led to more interest in my explosive works. Actually, it was by invitation, which I’m not proud of, but I was invited by Levi’s to do a project in Berlin. That allowed me to create the studio. I started to understand you can create something that is video and there’s a core message and a metaphor that you want to pass on.

I always thought your Levi’s project was a great example of how working with a brand can help foster creativity but you sound unenthused.

I try to do as little as possible. To do projects with brands that really understand the work and give me freedom, but it’s a compromise. That project allowed me to have a team, to set up a studio and to be able to pay people and have contracts and security. I didn’t have the funds to do that on my own so I see it as a means to an end but the [brand project] needs to respect you as well. I’m always very cautious of the commodification of the whole scene but sometimes you need to deal with it to sustain your practice.

Your early days as an artist were spent in the streets. What’s your perspective on street art these days?

There was a period of time that all we wanted was recognition for our work. Now the challenges are different. As the mainstream begins to understand what we can bring to a city, it becomes challenging. Instead of creating value to the community and bringing art to the people, artists are being used as a force of gentrification. I think a lot of real estate companies and even councils understand the power of culture. As an artist, I’ve become more conscious about that. This is why I take more time to decide which projects, to know who is behind them and understand the consequences the work can have.

What originally drew you to graffiti?

Graffiti was big here, especially for kids. A lot of my friends were doing it in the early days of school: bombing, throw-ups, letters and trains. It’s normal when you’re growing up. It’s a way for you to belong and to investigate yourself and to prove to yourself that you’re capable. I was rebellious but it wasn’t really political. I wasn’t really trying to get any messages across the way I do today. In a way it saved my life because to be honest, I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t do this, so I’m happy I didn’t give up.

And you’re a museum artist now. What’s it like doing projects with museums?

I mean it’s still quite difficult to deal with institutions. I don’t think they are completely open to the movement and I don’t think they really understand everything that’s happening. Which is good. In the project we did in Cincinnati [at Contemporary Arts Center], we blew up a wall inside the museum. That was quite challenging for them to accept. When I try to do something in a closed space, a gallery or an institution, I try to raise the same questions as when I work in a public space. I see it as try- ing to carve space for our community to get in and to be heard but it’s still a place where a lot of doors are closed. There are a lot of artists who came before me that should have recognition for what they achieved.

@vhils